Table of Contents

What is blood Transfusion?

Blood transfusion refers to the infusion of blood or blood components for the purpose of saving a life. Blood transfusion may be given to:

- Replace blood lost during surgery

- Replace a deficiency of specific blood components such as red blood cells (erythrocytes), platelets (thrombocytes) and clotting factors

- Increase the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, as in anaemia.

- To increase the intravascular volume in shock caused by bleeding.

Blood is collected from donors in containers containing anticoagulants to prevent the blood from clotting. The anticoagulant that is most frequently used is a mixture of sodium citrate, citric acid and dextrose (acid citrate dextrose – ACD). The sodium citrate prevents clotting. The citric acid serves as a preservative and the dextrose prolongs the lifespan of the red blood cells (erythrocytes). Heparin is also used as an anticoagulant in blood that is to be transfused within 24 hours of collection. Heparinized blood is necessary for extracorporeal shunts (as in open heart surgery). The heparin is less damaging to platelets and to the enzyme: 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (DPG), which promotes the release of oxygen from oxyhaemoglobin.

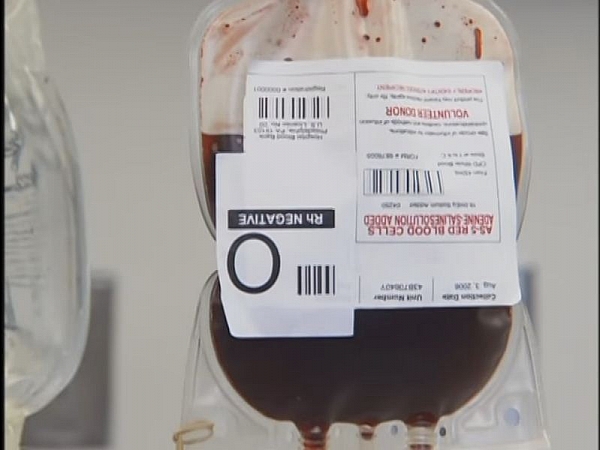

The collected blood is labeled clearly to indicate donor number, blood type, whether Rh positive or negative, anticoagulant used, and expiry date. The blood may be transfused as whole blood (containing all the components) or some of the components may be separated out for administration to meet the specific need of treatment while avoiding massive blood transfusion. Blood is stored at a temperature of 2-4oC and may be used within 21 days of having been obtained, except that which is heparinized.

Types of Blood transfusion

- Autologous blood transfusion (ABT)

- Donor-recipient blood transfusion

- Exchange blood transfusion (EBT)

Autologous blood transfusion (ABT)

This involves the collection and infusion of the patients own blood prior to any surgery or therapy. It may be an acceptable alternative to blood transfusion for Jehovahs Witnesses and has the specific advantage of involving no risk of transmission of viral infections such as HIV and hepatitis. There is no risk of a haemolytic reaction and ABT is useful for elective surgery if there is a shortage of donated blood. ABT involves collection of blood prior to surgery, or intraoperative salvage involving special recovery systems. These techniques however, are relatively uncommon and unlikely to replace the existing system of blood donation. Human recombinant erythropoietin is another alternative to blood transfusion and is currently being evaluated as a means of reducing the need for blood transfusion in some anaemic patients and for increasing the amount of autologous blood that can be collected prior to elective surgery.

Types of Autologous Blood transfusion

- Predeposit Autologous Blood Transfusion (PABT): The patient donates 2-5 units of blood at approximately weekly intervals before any elective surgery. This cannot be done in emergency cases.

- Preoperative haemodilution: 1 or 2 units of blood are removed from the patient just before the surgery and re-transfused to replace any blood loss while carrying out the surgery.

- Blood salvage: In this type, the blood that is lost during or after surgery may be collected by special techniques and re-transfused. Several techniques of varying levels of sophistication are available. The operative site must be free of bacteria, bowel contents and tumor cells.

Demand for pre-deposit autologous blood transfusion in the United Kingdom is not much as blood is generally perceived as being ‘safe’ and blood salvage is increasingly being used as a way of avoiding the use of donor blood, but in developing countries, autologous blood and blood from relatives are commonly used.

Types of Blood components used in blood transfusion

- Whole blood: whole blood is administered to replace blood loss or to increase the intravascular volume in shock caused by haemorrhage.

- Packed red cells: this type of blood component is gotten by removing a large portion of the plasma from whole blood by centrifugation. The remaining cells are then given to increase the oxygen carrying capacity of the recipients blood. The advantage of transfusion of packed cells is that lesser volume is added to the patients intravascular volume, hence, preventing the risk of circulatory overload. The cells may be transfused in a small volume of normal saline or plasma.

- Platelets (Thrombocytes): platelets may be concentrated and transfused in small volume to avoid the administration of a large volume of fluid. This avoids the risk of overloading the recipients heart and the circulatory system. Transfusion of platelets is used to control bleeding in patients with thrombocytopenia (low platelets in the blood). ABO compatibility is not essential but the development of alloimmunization is a complication of platelet transfusions. The rate of platelet destruction is increased in the sensitized individual. Rh immunoglobulin is administered to Rh negative persons who receive platelets from an Rh-positive donor to prevent Rh sensitization.

- White blood cells (Granulocytes): White blood cells from an ABO compatible donor are prepared from the whole blood by a process called Leucophoresis. They are administered to neutropenic (low white blood cells in the blood) patients with persistent infection despite antibiotic therapy.

- Albumin: this is an important protein in the blood and it is prepared from plasma and is available in concentrations of 5% and 25% solutions. It is used to rapidly expand plasma volume in severe hypovolaemia (low intravascular volume). This is expensive.

- Clotting factors: concentrates of certain clotting factors such as factors VIII and IX are also prepared from fresh frozen plasma to control bleeding in haemophilia A and B or in fibrinogen deficiency. Preparations include cryoprecipitates and specific factor preparations.

Blood transfusion risks and complications

It has been mandatory in the United States to report any transfusion-associated deaths to the Food and Drug Administration; the reports have provided useful data which have contributed to the efforts made to improve the safety of blood transfusion. Other similar reports have been set up in other countries such as the Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) scheme in the United Kingdom under the term ‘haemovigilance’. SHOT scheme reports of 2002/03, indicated that ‘incorrect blood component transfused’ was the most frequent type of serious errors in blood transfusion. Errors in collection, administration of blood, laboratory errors and prescription of blood errors and the collection of blood samples for compatibility testing were the commonest. Death or serious morbidity can also be attributed to other complications of blood transfusion including transfusion-associated lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease (TA-GvHD), and bacterial infection of blood components.

A number of measures have been taken in the UK, including universal leucocyte depletion of blood components (in 1999) because the prion protein is thought to be primarily associated with lymphocytes.

UK donor plasma is not used for the manufacture of blood products; imported plasma from the United States is used instead. While stringent measures are being taken to minimize the risk of transfusion-transmitted infection in countries like the UK, it may never be possible to guarantee that donor blood is absolutely safe. The current approach to the safety of blood components and plasma in some developed countries is extremely cautious, but it is not an absolute guarantee of safety.

Clinicians should always carefully consider the patient’s requirement for transfusion, and only transfuse if clinically appropriate.

The transfer of blood or any component of it carries a risk of a reaction. The blood or its components may act as a foreign protein or antigen that prompts an immune response or tissue reaction. Unfavourable effects to blood transfusion are outlined below.

Blood transfusion risk and complications

- Haemolytic transfusion reaction

- Non-haemolytic (Febrile) reaction

- Allergic reaction

- Circulatory overload

- Infection

- Immunosuppression

Haemolytic transfusion reactions

This is agglutination of the donors red blood cells followed by their haemolysis, which occurs as a result of incompatibility. This process is known as Alloimmunization and is characterized by antibodies within the recipients blood attacking the donors red blood cells, white cells or platelets. Haemoglobin and other products of the haemolysis are circulated throughout the body.

Blood transfusion carries a risk of alloimmunization to the many ‘foreign’ antigens present on red cells, leucocytes, platelets and plasma proteins. Alloimmunization may also occur during pregnancy to fetal antigens inherited from the father and not shared by the mother.

Alloimmunization does not usually cause clinical problems with the first transfusion but these may occur with subsequent transfusions. There may also be delayed consequences of alloimmunization, such as Haemolytic Disease of the Newborn (HDN) and rejection of tissue transplants.

Immediate reaction. This is the most serious complication of blood transfusion and is usually due to ABO incompatibility. There is complement activation by the antigen-antibody reaction, usually caused by IgM antibodies, leading to rigors, lumbar pain, dyspnoea, hypotension, haemoglobinuria and renal failure. The initial symptoms may occur a few minutes after starting the transfusion. Activation of coagulation may also occur and bleeding due to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a bad prognostic sign. Emergency treatment may be needed to maintain the blood pressure and renal function.

Delayed reaction. This may occur in patients alloimmunized by previous transfusions or pregnancies. The antibody level is too low to be detected by pretransfusion compatibility testing, but a secondary immune response occurs after transfusion, resulting in destruction of the transfused cells, usually by IgG antibodies.

Haemolysis is usually extravascular as the antibodies are IgG, and the patient may develop anaemia and jaundice about a week after the transfusion, although most of these episodes are clinically silent. The blood film shows spherocytosis and reticulocytosis. The direct antiglobulin test is positive and detection of the antibody is usually straightforward.

Signs and symptoms of Early (immediate) haemolytic reactions

- local pain at the infusion site,

- chills,

- headache or full feeling in the head,

- Anxiety

- Restlessness

- Pain in the kidney area (backache)

- Chest pain

- Difficulty in breathing (dyspnoea)

- Tachycardia (fast heart beat)

- Palpitation (feeling of your heart beating)

- Anaphylactic shock: this manifests with cold and clammy, increased difficulty in breathing, pulse becomes weak.

In patients that have been anaesthetized, a haemolytic reaction can be difficult to detect.

Signs and symptoms of Late haemolytic reactions

- Haemoglobinuria (urine becomes red)

- Oliguria

- Anuria

- Acute renal failure

- Hyperkalemia

- hypocalcemia

Treatment: the administration of blood or blood component is stopped promptly with the initial manifestation(s) of reaction. The normal saline is started again slowly to maintain an open intravenous line in case medications may have to be administered intravenously. If the patient complains of shortness of breath and tightness in the chest, adrenaline 1:1000 (0.5-1ml) subcutaneously or intramuscularly may be prescribed. A marked fall in blood pressure (hypotension) may be treated by increasing the intravascular volume with a plasma substitute such as haemaccel.

The treatment is instituted to promote urinary output and reduce impairment or renal function by the haemoglobin released through haemolysis. The fluid intake and output must be accurately measured and recorded. An indwelling cathether may be passed so the urinary output may be measured hourly. Fluids containing potassium must be avoided. Intravenous solutions are administered and may include mannitol (an osmotic diuretic). If the urinary output progressively decreases, the fluid intake is limited to insensible fluid loss and losses by other channels (vomiting, bowel elimination). Anuria and renal failure may develop, necessitating haemodialysis.

Non-haemolytic (Febrile) reaction of blood transfusion

A fairly common reaction to a transfusion is fever preceded by a rigor. It is attributed to the recipients sensitivity to the donors leucocytes, thrombocytes or plasma proteins. It may also develop as a result of a pyrogenic material in the equipment or solution used. The transfusion is slowed to relieve the discomfort of the febrile reaction and chills. If the person has had multiple transfusions or experienced this type of reaction before, hydrocortisone and chloropheniramine (piriton), an antihistamine, may also be prescribed.

A febrile reaction may be the first sign of an acute haemolytic reaction or it may indicate that the blood or blood product was infected with live bacteria or bacterial toxins.

Febrile reactions are a common complication of blood transfusion in patients who have previously been transfused or pregnant. The usual causes are the presence of leucocyte antibodies in an alloimmunized recipient acting against donor leucocytes in red cell concentrates leading to release of pyrogens, or the release of cytokines from donor leucocytes in platelet concentrates.

Typical signs of Febrile reaction

- Flushing

- Tachycardia

- Fever (> 38C)

- Chills and rigors.

Aspirin may be used to reduce the fever, although it should not be used in patients with thrombocytopenia as it will increase the risk of bleeding.

The introduction of leucocyte-depleted blood in the United Kingdom, in order to minimize the risk of transmission of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) by blood transfusion, has reduced the incidence of febrile reactions.

Leucocyte antibodies in donors plasma, who are usually multiparous women(women who have carried pregnancy to term) , may cause severe pulmonary reactions (called transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI)).

Signs of TRALI

- Dyspnoea (difficulty in breathing)

- Fever

- Cough

- Shadowing in the perihilar and lower lung fields on chest X-ray.

Allergic reaction of blood transfusion

A component of the donors blood may act as an antigen and initiate an allergic response. It is also suggested that the cause of an allergic reaction may be the response of the antibodies in the donors blood to an antigen within the recipient. These reactions are common but rarely severe; The most common manifestations are urticarial and asthma. Severe bronchospasm and anaphylaxis occur less frequently. Anaphylaxis occurs in persons who are IgA deficient, who produce anti-IgA that reacts with IgA in the transfused blood. When such persons are sensitized, either by a previous pregnancy or transfusion, an anaphylactic reaction may occur with a transfusion of plasma containing blood products. Stopping or slowing the transfusion and administration of chlorphenamine (chorpheniramine) or diphenhydramine hydrochloride (Benadryl), may provide relief. If the bronchospasm is severe or anaphylaxis develops, epinephrine (adrenaline) may be administered parenterally as well as a corticosteroid preparation; endotracheal intubation may be required. Patients who have had severe urticarial or anaphylactic reactions should receive either washed red cells, autologous blood, or blood from IgA-deficient donors for patients with IgA deficiency.

Circulatory overload (Massive Blood transfusion)

The giving of a transfusion too rapidly, or the administration of whole blood or plasma to someone with a normal intravascular volume or who has or is predisposed to cardiac or renal insufficiency, is dangerous. The resulting increased intravascular volume places too great a demand on the heart. Heart failure and pulmonary oedema ensue. The patient develops severe dyspnea, coughing, anxiety, weak pulse and cyanosis. A pink frothy sputum is expectorated.

Massive Blood transfusion leading to circulatory overload may be prevented by the slow administration of packed cells while the central venous pressure is monitored carefully.

Non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema or adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) may also occur. This is likely to be due to a reaction to the HLA antibodies in the donor plasma.

Infection

Infected blood often causes chest and abdominal pain, and hypotension may occur (septicaemic shock). If this is suspected, antibiotic therapy is prescribed.

Hepatitis is the most common infectious problem associated with transfusion. Donors blood is tested in blood banks for the hepatitis B antigen, but the transmission of hepatitis is still a possibility. The onset of manifestations of the infection may occur many weeks after the transfusion.

Syphilis, Malaria, AIDS and hepatitis B, non-A and non-B may be transmitted by blood transfusion, but the possibility is minimal because of the screening of donors and the tests that are performed on all donor blood.

Donor questionnaires can be used for recording of recent travel to exclude possible risks of West Nile virus (WNV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Recently, WNV has been the causal agent of meningoencephalitis transmitted by transfusion or transplantation in the United States of America.

In the UK the incidence of transmission of HIV by blood transfusion is extremely low fewer than 1 in 8 million units of blood transfused. Prevention is based on self-exclusion of donors in ‘high-risk’ groups and testing each donation for anti-HIV before blood is collected.

There is still a potential risk of viral transmission from coagulation factor concentrates prepared from large pools of plasma. Measures for inactivating viruses such as treatment with solvents and detergents are undertaken. Viral transmission via blood transfusion is still a major issue in the developing world.

Bacterial contamination of blood components is rare but it is one of the most frequent causes of death associated with transfusion. Some organisms such as Yersinia enterocolitica can proliferate in red cell concentrates stored at 4C, but platelet concentrates stored at 22C are a more frequent cause of this problem. Systems to avoid bacterial contamination include automated culture systems and bacterial antigen detection systems, but none are currently in routine use in the UK.

Transfusion-transmitted syphilis is very rare in the UK. Spirochaetes do not survive for more than 72 hours in blood stored at 4 C, and each donation is tested using the Treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay (TPHA). There continues to be concern about the risk of transmitting the prion protein causing vCJD by blood transfusion: a possible transmission occurred following a transfusion in 2003.

Diseases transmitted through blood transfusion

- Malaria

- HIV/AIDS

- Cytomegalovirus infection

- Hepatitis B viral infections

- Hepatitis C viral infections

- Syphilis

- Visceral Leishmaniasis (Kala Azar) this is rare but can be transmitted

- West Nile virus

- Epstein Barr Virus

- Human T-Cell Leukaemia Virus type 1 (HTLV-1)

- South American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease)

- Babesiosis

- Prion vCJD

Immunosuppression

There may be transfusion induced immunosuppression but the mechanism through which this happens is unknown.

Treatment of blood transfusion reaction

When blood transfusion reaction occurs, this should be done:

- Stop the transfusion promptly.

- Slow infusion of normal saline is resumed

- The remaining blood or blood component is returned in the container with the tubing to the blood bank for analysis and determination of the cause of the reaction.

- Blood specimens are taken from a vein other than the one that was used to administer the blood. They are sent to the laboratory for grouping and cross matching, culture and free haemoglobin estimation in the plasma.

- Vitals signs are monitored frequently and continuous assessment of the patients condition is necessary.

- Urine specimen is collected from the patient as soon as possible and sent t the laboratory for haemoglobin determination

Blood transfusion ethics and Jehovahs Witness

Although blood transfusion is a commonly-used therapeutic procedure, it is necessary to bear in mind that a transfusion may be refused because of religious beliefs or other considerations. Refusal of blood and blood products on religious grounds is usually associated with Jehovahs Witnesses. Most courts have recognized the right of adult Jehovahs witnesses to refuse blood and blood products for themselves. However, it has usually been judged that parents and guardians do not have the right to refuse life-saving therapy (including blood transfusions) for thei minor children and a court order may be applied to protect a child. Whenever it becomes apparent that a patient is a Jehovahs Witness, the use of blood and blood products should be discussed with the patient, with a clear explanation of the consequences of refusing treatment. It is advisable to obtain a signed and witnessed statement or consent if treatment is refused.