BIRTH PREPAREDNESS AMONG URBAN PRIMARY HEALTH CARE CLINIC ATTENDEES IN JOS NORTH LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF PLATEAU STATE

BY: BONGDAP NANSEL NANZIP

DAPAN PAUL YUSUFU

DAPAN PETERYUSUFU

A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY MEDICINE, FACULTY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF JOS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF BACHELOR OF MEDICINE, BACHELOR OF SURGERY (M.B.B.S) DEGREE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF JOS, NIGERIA.

JULY, 2016.

Table of Contents

- DECLARATION

- CERTIFICATION

- DEDICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

- ABSTRACT

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- 3.0 METHODOLOGY

- 3.1 STUDY AREA

- 3.2 STUDY POPULATION

- 3.2.1 INCLUSION CRITERIA

- 3.2.2 EXCLUSION CRITERIA

- 3.3 STUDY DESIGN

- 3.4 SAMPLE SIZE DETERMINATION

- 3.5 SAMPLING TECHNIQUE

- 3.6 INSTRUMENTS OF DATA COLLECTION

- 3.7 PREPARATION FOR DATA COLLECTION

- 3.8 DATA COLLECTION

- 3.9 DATA ANALYSIS

- 3.10 SCORING CRITERIA

- 3.11 ETHICAL CONSIDERATION

- 3.12 LIMITATION OF STUDY

- 3.0 METHODOLOGY

- CHAPTER FOUR

- SCORING CRITERIA FOR ASSESSING KNOWLEDGE OF BIRTH PREPAREDNESS AMONG RESPONDENTS

- CHAPTER FIVE

- CHAPTER SIX

- REFERENCES

DECLARATION

We the above listed hereby declare that this is our original work done under appropriate supervision, and that it has not been presented in part or whole for another examination or award for another degree.

CERTIFICATION

This is to certify I supervised this project and it certifies the criteria required for the award of Bachelor of medicine, Bachelor of surgery (MBBS) degree of the University of Jos, Nigeria.

___________________ __________________

DR. H.A AGBO Date

Project Supervisor

___________________ __________________

DR. M. P. CHINGLE Date

Head, Department of Community Medicine,

University of Jos.

DEDICATION

We dedicate this work to God Almighty who made it possible from the beginning to the end amidst all the challenges we faced and to our Parents for their prayers, financial support and love, without them, this would not have been possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to God for giving us the grace to work together as a project team. We especially thank our supervisor, Dr. Agbo H.A for her indefatigable support throughout the period of ourresearch. We also thank the Head of department, Community Medicine, University of Jos, Dr. Chingle M.P and other lecturers in the department for imparting us with invaluable knowledge. We thank the following pillars of our careers for their constant encouragement and all round overwhelming support: Mrs Naomi Bongdap and Family, Mr. and Mrs. Yusufu Dapan and Siblings. Finally, we express our profound gratitude to the management of Jos University Teaching Hospital, JUTH for giving us access to the respondents. We want to appreciate the pregnant women who participated in this study.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title page – – – – – – – – –

Declaration – – – – – – – – –

Certification – – – – – – – – –

Dedication – – – – – – – – –

Acknowledgement – – – – – – – – –

Table of contents – – – – – – – – –

Abstract – – – – – – – – –

CHAPTER ONE

1.0 Introduction – – – – – –

1.1 Background – – – – – –

1.2 Statement of problem – – – – – –

1.3 Rationale of study – – – – – –

1.4 Aims and Objectives – – – – – –

1.4.1 General objective – – – – – –

1.4.2 Specific objective – – – – – –

1.5 Hypothesis – – – – – –

1.5.1 Null Hypothesis – – – – – –

1.5.2 Alternate Hypothesis – – – – – –

CHAPTER TWO:

2.0 Literature Review – – – – –

2.1 Introduction – – – – –

2.2 Knowledge of Birth Preparedness – – – – –

2.3 Institutional Measures for birth preparedness – – – –

2.4 Barriers and Facilitators to Birth Preparedness – – – –

CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY

3.0 Methodology – – – – – –

3.1 Study Area – – – – – –

3.2 Study Population – – – – – –

3.3 Study Design – – – – – –

3.4 Sample Size – – – – – –

3.5 Sampling Technique – – – – – –

3.6 Instruments of Data Collection – – – – – –

3.7 Preparation for Data Collection – – – – – –

3.8 Data Collection – – – – – –

3.9 Data Analysis – – – – – –

3.10 Scoring Criteria – – – – – –

3.11 Ethical Consideration – – – – – –

3.12 Limitation of study – – – – – –

CHAPTER FOUR:

4.0 Results – – – –

4.1 Socio-demographic Characteristics – – – –

4.2 Knowledge of Birth Preparedness – – – –

4.3 Institutional Measures put in place for Birth Preparedness – – – –

4.4 Barriers and Facilitators to Birth Preparedness – – – –

CHAPTER FIVE:

5.0 Discussion – – – – – – –

5.1 Socio-demographic Characteristics – – – – – – –

5.2 Knowledge of Birth Preparedness – – – – –

5.3 Institutional Measures for Birth Preparedness – – – – –

5.4 Barriers and Facilitators to Birth Preparedness – – – – –

CHAPTER SIX:

6.1 Conclusion – – – – – – – –

6.2 Recommendation – – – – – – – –

REFERENCES – – – – – – – – – –

APPENDIX – – – – – – – – – –

ABBREVIATIONS

ANC – – – – Antenatal Care

BP/CR – – – Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

JUTH – – – Jos University Teaching Hospital

OR – – – Odds Ratio

SPSS – – – Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

CI – – – Confidence Interval

MDG – – – Millennium Development Goals

PHC – – – Primary Health Care

WHO – – – World Health Organisation

UBTH – – – University of Benin Teaching Hospital

NDHS – – – National Demographic and Health Survey

MMR – – – Maternal Mortality Ratio

LGA – – – Local Government Area

IEC – – – Information, Education and Communication

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Tables:

Table 1: Socio-demographic factors

Table 2: Assistance given to respondents in preparation for safe delivery

Table 3: Institutional measures for Birth preparedness

Table 4: Plans made for Delivery

Table 5: Assistant in making plans for safe delivery

Table 6: Relationship between Educational status and Knowledge of birth preparedness

Table 7: Relationship between number of deliveries and Knowledge of birth preparedness

Table 8: Relationship between Age of respondents and Knowledge of birth preparedness

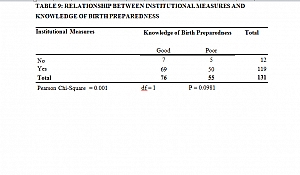

Table 9: Relationship between Institutional measures and Knowledge of birth preparedness

Figures:

Figure 1: Pie chart showing the age for commencing ANC among respondents

Figure 2: Bar chart showing the measures taken by the respondents to prepare for safe delivery

Figure 3: Pie chart showing the assistants in the preparation for safe delivery

Figure 4: Bar chart showing danger signs of pregnancy known by respondents

Figure 5: Pie chart showing if ANC clinic has been of help to respondents or not

Figure 6: Pie chart showing respondents that have made adequate plans or not

Figure 7: Knowledge of birth preparedness among respondents

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

A significant proportion of women in the developing world suffer from different illnesses during pregnancy and child birth, thereby increasing the burden of maternal mortality. These avoidable problems are often encountered because of the lack of knowledge of birth preparedness which is a key component of the globally accepted safe motherhood programmes.

OBJECTIVE

This study therefore aims to access the current status of the knowledge of birth preparedness among pregnant women attending antenatal care in urban primary health care of Jos North LGA.

METHODOLOGY

A descriptive cross-sectional study using multi-stage sampling technique recruited 131 pregnant women (18-45 years) attending antenatal clinic in Jos North LGA, Plateau State between March to June 2016. A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was employed to obtain relevant information on the knowledge of birth preparedness and data was analysed using SPSS 18.0 software.

RESULTS

The study showed that 58.02% of the respondents had good knowledge of birth preparedness. 90.84% of respondents admitted that the health centre has been of help to them in regards to birth preparedness.

CONCLUSION

The knowledge of birth preparedness is adequate among respondents and this can be attributed to high level of Education of respondents.

CHAPTER ONE

1.0 INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND

Child birth is a universally celebrated event but for many thousands of women each day this experience is tailored with not much to be desired health challenges especially in the developing countries. Globally, about 40% or more of pregnant women experience acute obstetric morbidities such as haemorrhage, sepsis, and pregnancy related hypertension or long term morbidities such as uterine prolapse, vesico-vaginal fistula, urinary incontinence, dyspareunia and infertility.1 In an effort to minimize the likely complications that may occur during pregnancy and in the process of child birth, the concept of birth preparedness evolved. Birth preparedness is the process of planning for normal birth and anticipating the actions needed in case of an emergency, thereby reducing the incidence of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The concept of Birth preparedness includes identifying skilled provider and making the necessary plans to receive skilled care; knowing danger signs; selecting a birth location and preparing for rapid action in the event of obstetrics emergency. Such emergency plan should include identifying the nearest functional 24hrs emergency obstetrics care facility, making arrangement for transportation to a care facility or in case of a referral, suitable blood donor in case of haemorrhage, sourcing funds for emergency.2 Birth preparedness is an important component of Focused Antenatal Care which involves planning with the key stakeholders, the health provider, pregnant women and relatives and the community.3 The principle of birth preparedness if adequately put into practice have the potential of reducing the existing high maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality rates. It promotes skilled care for all births and encourages decision making before the onset of labour. It also creates awareness of danger signs, thereby improving problem recognition and reducing delay in deciding to seek care. It provides information on appropriate sources of care (facilitators) making the care-seeking process more efficient and with fewer barriers. It also encourages households and communities to set aside money for transport and service fees, avoiding delays in reaching health facilities where care could be sought, which are often caused by financial constraints.4 Birth preparedness helps ensure that women can reach professional delivery care when labour begins and reduces the delays that occur when women experience obstetrics complications.5 Birth preparedness raises the awareness of danger signs in pregnancy thereby improving problem recognition and enabling women decide in seeking medical care. Maternal and neonatal services in turn help ensure that antenatal attendees are given easy access to skilled health care providers. Making arrangements for blood donors is also important because women giving birth may need blood transfusions in the event of haemorrhage of caesarean section.6 Birth preparedness is facilitated in the urban areas by availability of Primary Health Care centres where skilled care givers are employed and women are educated about the importance of making preparations towards birth. Other facilitators may include accessible road networks and means of transportation and ease of referral to other higher specialized centres in times of complications. However, poverty, illiteracy, poor road networks and lack of skilled care givers are barriers to birth preparedness.7

STATEMENT OF PROBLEM

Maternal mortality is a substantial burden in developing countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 500,000600,000 women die from pregnancy and childbirth-related complications each year, with 99% of these deaths occurring in developing countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, the maternal mortality ratio is 920 per 100,000 live births, and the lifetime risk of maternal death is 1 in 16 compared to 1 in 2,400 in Europe.8 Nigeria presently is 2% of the worlds population but accounts for 10% of maternal deaths globally, ranking it second to India. Its recent National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) data highlights different mortality ratios even within its six geopolitical zones, which were also supported by another population based study which indicated that this mortality ratio is worst recorded in the northern parts of the country with an average figure of 2,420 per 100,000 live births in Kano.9,10 In the North eastern region, Borno state has an estimated maternal mortality ratio of 1,549 per 100,000 live births while in Bauchi state, maternal mortality ratio was reported as 1,732 per 100,000 live births which are the worst in the world.11,12 In Plateau state, North central region of Nigeria, maternal mortality ratio was 740 per 100,000 live births was reported. The rates for urban and rural communities in Plateau state are 450 and 1,320 deaths per 100,000 live births and a life time risk of 0.278 and 0.838 respectively.13,14 According to the NDHS, these figures can be attributed to poor health care seeking behaviours as seen among many pregnant women, bottlenecks involved in transportation (poor road networks, far distances of rural settlements to health facilities) and inadequate skilled providers in northern parts of Nigeria.15

RATIONALE FOR THE STUDY

Every pregnant woman faces the risk of sudden unpredictable complications that could end in death or injury to herself or to her infant. Birth preparedness is the strategy that encourages pregnant women, their families and communities to effectively plan for birth and deal with emergencies if they occur. An assessment of the concept of birth preparedness among urban PHC clinic attendees may provide a fair clue about the level of awareness among pregnant women and gaps identified from this study may help to proffer solution to creating more awareness through health education at antenatal and post natal clinics by the health care providers.

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

General

To assess the awareness and willingness of birth preparedness among urban Primary Health Care clinic attendees in Jos North LGA of Plateau State.

Specific

- To assess the knowledge of birth preparation among the clinic attendees

- To determine the institutional measures put in place for birth preparedness

- To determine barriers and facilitators to birth preparedness among the clinic attendees

HYPOTHESIS

Null Hypothesis

Clients attending antenatal clinic do not possess a good knowledge of birth preparedness, if they do; it is by chance.

Alternate Hypothesis

Clients attending antenatal clinic possess a good knowledge of birth preparedness, which is real.

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

INTRODUCTION

Birth Preparedness is a strategy which promotes timely use of skilled maternal and neonatal care especially during child birth, in order to avert likely complications that could arise.16 Birth preparedness is a common strategy employed by numerous groups implementing safe motherhood programs. Some of the standard elements of birth preparedness are knowledge of the danger signs, choosing a birth location and provider, knowing the location of the nearest skilled provider, obtaining basic safe birth supplies, and identifying someone to accompany the woman. It also includes arranging for transportation, money, and a blood donor. The emphasis is on the demand side that is, the individual, family and community, or the users of healthcare services. The Maternal and Neonatal Health (MNH) Program has expanded the concept of Birth preparedness to address also the supply side of the equation, that is, the provider, the facility and the policymaker. Inclusion of these additional levels indicates that factors causing delays in seeking care for obstetric emergencies arise from many different sources, and therefore require action from actors across multiple levels of society.

Knowledge of Birth preparedness among antenatal attendees

The knowledge of birth preparedness is important in ensuring that women make adequate preparation in handling unforeseen events that may arise during delivery, where this knowledge and its application is deficient, complications arising during delivery can lead to maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. According to a study conducted in Indore slum by Siddharth et al showed that 47.8% of the mothers with children between 2 and 4 months had been well prepared during pregnancy.17 Also, a study conducted by 3 David PU in Mpwapwa district, Tanzania in 2012, 86.2% of the women had made decisions on place of delivery, 68.1% of the women planned to be delivered by skilled attendant and only 8.7% women arranged for a potential blood donor.18 In West Java, Indonesia, knowledge of danger signs and birth preparedness among ANC clinic attendees revealed that awareness through the channels of mass communication leads to well informed decisions about severe bleeding as a danger sign as well as increased birth preparedness and antenatal behaviours. 19 A study in Malawi showed that fifty-eight percent (58%) of the primigravida had some knowledge and could make an informed decision to go to a health facility with pregnancy complications.20 According to a study by Ibrahim et al. in Southwest Nigeria among ANC attendees, only 38% of the respondents revealed some level of awareness of birth preparedness. This is lower than 70.6 % reported from a similar study conducted by John et al. from another region in this country. The awareness of birth preparedness among ANC attendees was better in University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH) than central hospital because UBTH respondents were more enlightened on birth preparedness and 39.3% of them could correctly explained the meaning of the term as against 27.3% of central hospital ANC attendees. Another study conducted in Kenya showed that 67% of pregnant women attending ANC clinic are enlightened about birth preparedness, this figure is higher than in the study conducted in UBTH above.21

Institutional measures put in place for Birth preparedness

For birth preparedness to be effective at provider level, nurses, midwives, and doctors must have the knowledge and skills necessary to treat or stabilize and refer women with complications, and they must employ sound normal birth practices that reduce the likelihood of preventable complications. In 2006, the Nepalese Government introduced the National Policy on skilled birth attendants, which generally aimed to reduce maternal/neonatal morbidity and mortality by ensuring availability, access, and utilization of skilled care at every birth. This policy embodies the Governments commitment to train and deploy doctors, nurses, and auxiliary nursemidwives across Nepal.22In 2005, the Government of Nepal launched the Maternity Incentives Scheme, currently known as the Safe Delivery Incentive Program, to encourage women to use health facility services for childbirth. Women who deliver a baby in a health facility receive a pro-rated cash incentive for transportation, based on ecological region. Thus, women who use delivery services at a health institution in the mountain, hill, and terai (plains) regions receive Nepalese rupees (NRP) 1,500, 1,000, and 500 (1 US$ NRP 95 in June 2014), respectively. Importantly, this program provides no-cost delivery services at health facilities in districts ranked low on the Human Development Index.23 Pregnant women should have a written plan for birth and for dealing with unexpected adverse events that may occur in pregnancy, delivery or immediate postpartum period. This plan can be written in the birth preparedness card and reviewed with a skilled attendant at each antenatal. The birth preparedness card is a sample card designed to help mothers and families prepare for birth. It contains information on the expected date of delivery, place of delivery, birth attendant, transport arrangement, saving for birth cost, list of possible complications, antenatal visit, postnatal visit, etc. Programs in Egypt, Bangladesh and other countries have developed birth preparedness card and some others have developed guides to using the card and record keeping.24,25 In Tanzania, a sub-Saharan country, the government has introduced individual counselling of pregnant women on Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BP/CR) which is aimed at encouraging women and families to make decisions before the onset of labour and in case of obstetric complications by creating an awareness of the knowledge of danger signs, identifying a mode of transport, saving money, identifying a skilled attendant, identifying where to go in case of complications, and identifying a blood donor.26

Barriers and Facilitators to Birth preparedness

From various studies carried internationally and locally, some factors have been identified to facilitate or limit the preparation of women towards delivery. These factors are outlined below.

Male involvement

Male involvement in pregnancy care refers to all the care and support that men give to their partners who are pregnant or experiencing the outcome of pregnancy in order to avoid death or disability from complications of pregnancy and childbirth.Because patriarchy invests men with the power to determine what their wives do or fail to do, men often have control over women’s access to and utilization of maternal health services.27 Internationally, the realization of the need to promote the involvement of men in birth preparedness has seen many efforts geared toward achieving it. For example, an attempt was made to examine the level of involvement of husbands in birth preparedness in Nepal using the data drawn from Nepal Demographic Health Survey.In exploring the effect of various interventions on improving birth preparedness, a study conducted in Nepal found that joint health education of women and their husbands improved birth preparedness practice among them.22,27In Zimbabwe, theMiraNewakoProject engaged pregnant women and their husbands through a number of interventions, including community outreach, clinic-based education and couple-oriented counselling.The project reported improvement in male involvement behaviours among men who received couple-oriented counselling and/or community outreach and were given the Information, Education and Communication (IEC) materials, unlike among men who only received IEC materials.28 In Nigeria, a number of studies have found low level of male involvement in birth preparedness.29-31

Money

A study in India showed that majority (76.9%) of the families saved some money and kept it aside for incurring cost of delivery and obstetric emergencies, if needed. For the remaining 23.1% of the families, meagre earnings which were mostly spent on household purchases (16.7%) or by husband on liquor (6.4%) were cited as reasons for not saving money.32 In a Nigerian study, 41% of the mothers who did not deliver in hospital explain that they could not afford the hospital bills. Financial constraint in Nigeria is a major obstacle to accessing skilled attendants during pregnancy. It is therefore appropriate for pregnant women to save money for child birth and to be able to access emergency funds when needed.33

Education and Women Empowerment

A woman who is educated is able to make informed decisions about her own health compared to her illiterate counterpart.34 This is in line with the findings of other study conducted where education, occupation and income were among the factors affecting birth preparedness and complication readiness.35,36 The reasons could be, having high education, being employed and merchant are directly related with high access to information and income which enable them to be prepared for birth and its complications.

Distance

A study from Nepal among ANC clinic attendees showed that a distance of more than an hour to the maternity hospital was statistically associated with an increased rate of home delivery.37 According to the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, distance was an issue in seeking skilled attention. Up to half of the women living in rural areas have to travel up to 2km or more to reach the nearest hospital.38

Transportation

In a Nigerian study, 31% of ANC clinic attendees said they had transportation challenges and commonly use motorcycle as means of transportation to hospital. Transportation is a major challenge in Nigeria especially to pregnant as road networks are poor in many urban areas and virtually non-existent in most rural areas. In addition, the transport system is inefficient and not always available when needed. A study in Cross River State, Nigeria showed that families always incur long delays in finding means of transport to the nearest health facility.39

Culture and Beliefs

A research in Homabay and Migori, south western Kenya among ANC attendees showed that many of the study participants, young and old, viewed birth preparedness as a bad omen, an action that could actually create problem for the expectant woman. This is common in many other settings where taboos and superstitious beliefs discourage women and their families from preparing for emergencies.40

CHAPTER THREE

3.0 METHODOLOGY

3.1 STUDY AREA

The study was carried out among pregnant women in Jos North Local Government Area(LGA) of Plateau state which is one of its seventeen LGAs and its main metropolitan. It extends over an area of 291km2 with a total population of 429,300, projected from the 2006 National Population and Housing Census, with 266,66 (62%) being urban dwellers and 163,134 (38%) rural dwellers.41 In 2009, the National Population Commission estimated population of Jos North LGA as 439,217 comprising of 220,856 males and 216,361 females. It was estimated that 3000 pregnancies occurred per annum.41 The LGA shares boundaries to the west with Bassa LGA, to its North with Toro LGA of Bauchi state, to its East with Jos East LGA and Jos South LGA southward. Jos North LGA was created in 1987 with twenty political wards: Tafawa Balewa, Aba Nashehu, Ahwol, Alikazaure, Angwan Rogo/Rimi, Gangare, Garba Daho, Ibrahim Katsina, Jenta Adamu, Jenta Apata, Jos Jarawa, Kabong, Lamingo, Mazah, Naraguta A, Naraguta B, Rigiza/Targwong, Sarki Arab, Tudun Wada and Vander Puye.41

Jos is an administrative and cosmopolitan city consisting of diverse ethnic groups including Berom, Anaguta, Mwaghavul, Ngas, Rukuba, Irigwe. There are also Hausa, Fulani, Yoruba, Igbo and other minorities. Civil service, farming, small scale business are the predominant occupation and majority of the population are members of the Christianity or Islam religions.

In Jos North LGA there are twenty nine (29) Primary Health Care (PHC) centers, Plateau Specialist Hospital, Jos University Teaching Hospital, and over 40 private institutions including Bingham University Teaching Hospital, Our Lady of Apostle Hospital, Faith Alive Foundation.41

The study was carried out in the Township PHC located on Pankshin Street adjacent Rwang Pam Stadium in Tafawa Balewa ward. The PHC clinic has five sections including ANC which records about 1,500 new pregnancy visits each year. The clinic operates from Monday to Friday between 8 oclock am and 4 oclock pm.

3.2 STUDY POPULATION

The study was carried out among pregnant women of 15 to 45 years in their third trimester attending ANC at PHC Township, Jos North LGA.

3.2.1 INCLUSION CRITERIA

The study included pregnant women in the reproductive age group (15-45 years) attending ANC in Jos North LGA whom were accessible to us at Jos Township PHC and willing to participate in the study.

3.2.2 EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Pregnant women younger than 15 years and pregnant women older than 45years and those within this age group who do not give consent to be included in the study.

3.3 STUDY DESIGN

The study design was a descriptive cross-sectional study designed to find out birth preparedness among pregnant women attending ANC in Jos North LGA, Plateau state.

3.4 SAMPLE SIZE DETERMINATION

The minimum sample size was determined using the formula:

N=Z2pq/d2

Where N = minimum sample size

Z = standard deviation at 95% confidence interval = 1.96

p = prevalence of birth preparedness in Nigeria = 9.4%

Prevalence42 = 9.4% = 0.094

q = complementary probability = 1- p

q = 1 0.094 = 0.906

d = absolute precision (error tolerance of 5% = 0.05)

Therefore:

N = [(1.96)2 x 0.094 x 0.906]/(0.05)2

N = 130.8

N 131

The minimum random size was then rounded to a total of 264 pregnant women.

3.5 SAMPLING TECHNIQUE

Multistage sampling procedure was used to select study subjects.

STAGE 1: Jos North LGA was selected out of seventeen LGAs in Plateau state through a simple random sampling technique by balloting.

STAGE 2: Jos Township PHC was selected from the list of all the PHCs in the LGA through a simple random sampling technique by balloting.

STAGE 3: Using systematic sampling technique, a sampling interval of 11 was obtained by dividing the sampling frame of Jos Township PHC ANC attendance (1500) by the minimum sample size (131). From the clinics ANC register, every 11th subject was selected to give a total of 131 pregnant women.

3.6 INSTRUMENTS OF DATA COLLECTION

Data was collected through the use of semi-structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was divided into four sections:

Section A: Socio-demographic data

Section B: Knowledge of birth preparedness

Section C: Institutional measures put in place for birth preparedness

Section D: Barriers and Facilitators to birth preparedness

3.7 PREPARATION FOR DATA COLLECTION

Prior to the data collection, permission was sought and obtained from the office of the Chairman of Jos North Local Government Area, the coordinator in-charge of the Township PHC. Informed verbal consent was also sought and obtained from the study participants.

3.8 DATA COLLECTION

A pre-tested structured interviewer administered questionnaire was employed to obtain the relevant information. Questionnaires were administered on all the clinic days from Monday to Friday until the required minimum sample size was obtained.

3.9 DATA ANALYSIS

Data was collected, entered and analysed using SPSS version 18.0. The results were summarized in frequency tables. Statistical tests such as chi-square test, and measures of associations (odds ratio (OR) with P-value of 0.05 and 95% confidence interval (CI)) were used as deemed necessary.

3.10 SCORING CRITERIA

The study considered that knowing at least three danger signs of birth preparedness was referred to as having an adequate knowledge on birth preparedness. Similarly, birth preparedness score was computed from key elements of birth preparedness such as the arrangement for transportation, saving money for delivery, identifying skilled attendants to assist at birth, identifying a health care facility and identifying blood donor in case of emergency. Taking at least two of the steps mentioned above was considered being well prepared.

3.11 ETHICAL CONSIDERATION

The permission to conduct the research was obtained from the Department of Community Medicine of the University of JUTH, which was duly supervised by the Consultant to ensure all research ethics were strictly adhered to.

3.12 LIMITATION OF STUDY

This research has achieved its aim. However, the information we obtained from the respondents about their knowledge of birth preparedness could not be verified. Further empirical evaluations might be needed to validate such sensitive information.

CHAPTER FOUR

RESULTS

SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF RESPONDENTS

A total of 131 pregnant women attending ANC were recruited into the study. The ages range from 18-42. There were 125 (95.4%) married women, 5 were singles and 1 was divorced.

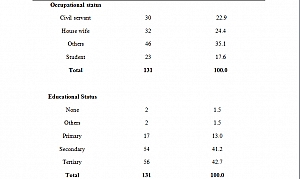

Civil servants were 22.9 %, House wives made up 24.2% while Students were 17.6% with the remaining percentage such as Business women.

In terms of Education, majority of respondents, 56 (42.7%) had tertiary education, 54 (41.2%) had secondary education, 17 (13.0%) had primary education, 2 (1.5%) had other forms of education such as Quranic with only 2(1.5%) having no formal education.

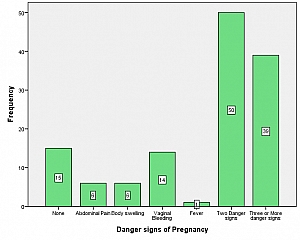

The predominant religion was Christianity, 74 (56.5%) while the rest were Muslims.

62.6% of the respondents suggested 3-4months to be the right age of gestation for commencement of ANC visit, 29% suggested 1-2 months while 8.4% suggested more than 4 months.

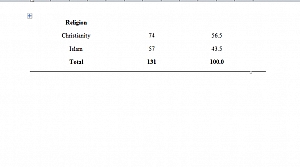

30 (22.9%) respondents suggest regular ANC visits and good diet to be the approriate measure for safe delivery, 27(20.6%) sugggested regular ANC as the only measure for safe delivery whereas 17(13.0%) respondents suggested regular ANC visits, good diet and exercise to be the measures for safe delivery.

57.3% of respondents had Health personnels that would help them prepare towards safe delivery, 32.1% had Family members, 2.3% had both Family members and Health personnels while 8.4% had no one to help them in preparation towards safe delivery.

62 (47.3%) respondents had assistants that could provide professional medical care towards preparation for safe delivery, 20 (15.3%) had enough assistants that could provide finance, while 14 (10.7%) had people that could help with counseling, 21(16.0%) had other forms of assistance such as transportation and prayers, but 14 (10.7%) had no any form of assistance that could help them prepare for safe delivery.

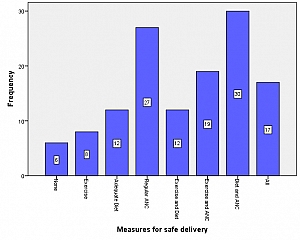

6 (4.6%) of the respondents mentioned severe abdominal pain and body swelling to be the danger sign they know, 14(10.7%) mentioned vaginal bleeding, only 0.8%(1) mentioned fever alone. 50(38.2%) of the respondents know two danger signs while 39 (29.8%) know three or more danger signs.

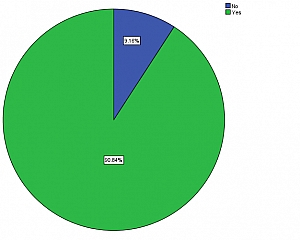

90.84% of respondents admitted that the health centre has been of help to them while 9.16% disagreed.

Of the 90.84% who agreed to have been helped by the health centre, 32(24.4%) says they were thought of the danger signs of pregnancy and other facts about pregnancy, 31(23.7%) says they were counseled on the problems related to pregnancy, 11(8.4%) says they were given list of items needed for delivery. 19(14.5%) were counseled and given list of items, 17(13.0%) were thought and given list of items needed for delivery and only 9(6.9%) were thought and counseled about pregnancy.

When asked if the respondents had made adequate plans for safe delivery, most of them, 89.31% said they had made adequate plans for delivery with the remaining had not made plans but intend to.

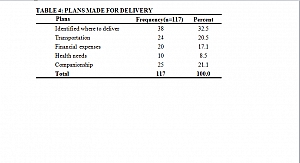

38(32.5%) of the respondents had identified a suitable place of delivery, 24(20.5%) had made arrangement for transportation, 20(17.1%) had saved money for financial expenses needed in case of any emergency, 10 (8.5%) have made arrangements for health needs such as having a suitable blood donor while 25 (21.1%) have someone who will help them at the hospital after delivery.

Of the 117 women, 16.0% have made two plans while 71.8% had made three or more plans.

Regarding having support towards preparation for safe delivery, most of the women, 80(61.1%) had support from their spouse, 16(12.2%) had support from other friends and relatives, 10(7.6%) had support from their mothers while 2(1.5%) had no support from any one.

SCORING CRITERIA FOR ASSESSING KNOWLEDGE OF BIRTH PREPAREDNESS AMONG RESPONDENTS

A total score of 10 was used. With the criteria as follows:

- Age of pregnancy for commencing ANC visit: age of less than or equals 4 months has a score of 2 while age of greater than 4months has a score of 0.

- Measures for preparation of safe delivery:

Knowing – 1measure = 1score

2 measures = 2 scores

3 measures = 3 scores

The measures were Exercise, Regular ANC visit and Adequate diet - Having an assistant for helping with preparation for safe delivery = 1 score while having none is a score of 0

- Knowledge of dangers of pregnancy:

Knowing – 1 sign = 1 score

2 signs = 2 scores

3 signs = 3 scores

More than 3 signs = 4 scores

Danger signs were: Body swelling, Severe abdominal pain, Fever, Absent foetal movement and drainage of liquor.

A score of 5 or more shows good knowledge while a score of less than 5 is regarded as poor knowledge.

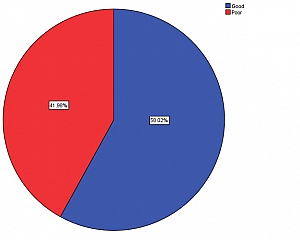

Using the scoring criteria above, 58.02% of the respondents had good knowledge of birth preparedness while 41.98% had poor knowledge.

The relationship between educational status and knowledge of birth preparedness was statistically significant, (X2 = 11.344, df = 4, P = 0.023 )

The relationship between number of deliveries and knowledge of birth preparedness was statistically significant, (X2 = 10.284, df = 3, P = 0.016)

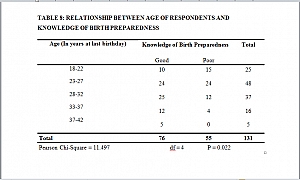

The relationship between age of respondents and knowledge of birth preparedness is statistically significant, (X2 = 11.497, df = 4, P = 0.022)

The relationship between institutional measures and knowledge of birth preparedness has no statistical significance, (X2 = 0.001, df = 1, P = 0.0981)

CHAPTER FIVE

5.0 DISCUSSION

5.1 SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Most of the respondents were bewteen the age group 23-27 which represented 36.5% of the study population. This satisfactorily captures the most active reproductive age. A ressearch carried out in Nigeria showed 54.5% of the respondents to be between the age group of 26-35 years.43

5.2 KNOWLEDGE OF BIRTH PREPAREDNESS

This study showed that 58.02% of the respondents were aware of planning and preparing for safe delivery, this is in keeping with a similar study in Ethiopia were 65% of the respondents were aware of birth preparedness.44 In a similar study carried out in Kenya 52% of the respondents were aware of birth preparedness.45 This shows that the level of awareness of birth preparedness is relatively high in Africa.

The study showed that 88.5% of the respondents were aware of danger signs during pregnancy, this may be because 41.2 % and 42.7% of the women had secondary and tertiary level of education as there was statistical significance between educational status and knowledge of birth preparedness while 11.5% were not aware of any danger sign. The most popular danger sign was Vaginal bleeding which was reported by 10.7% of the respondents. This is similar to a study done in Nigeria and Gambia when 19% and 14.8% respectively were aware of vaginal bleeding as a danger sign.46 However, 4.6% were aware of severe abdominal pains, 4.6% were also aware of body swelling and 0.8% were aware of fever; this is in keeping with the findings from study in Gambia were 4.9% were aware of fever and 24.5% were aware of body swelling.47 From our study, 29.8% of the respondents knew three or more danger signs in pregnancy, this higher than the findings in a study conducted in Kenya where only 6.9% of the respondents knew three or more danger signs in pregnancy.48

5.3 INSTITUTIONAL MEASURES FOR BIRTH PREPAREDNESS

From our study, 90.84% of our correspondents agreed that the clinic has been of help to them while 9.16% have not received any form of assistance as regards to birth preparedness. Of the respondents who agreed that they had assistance from the clinic, 23.7% received assistance via counselling on birth preparedness, this is in keeping with a study conducted in Tanzania where the government has introduced individual counselling of pregnant women on birth preparedness which is aimed at encouraging women and families to make decisions before the onset of labour in and incase of obstetrics complications by creating an awareness of the knowledge of danger signs, identifying a mode of transport, saving money, identifying a skilled attendant and identifying a blood donor.26 In our study, 24.4% of the respondents had health education via teaching sessions organised by the nurses in the ANC clinic.

From our study, there was no significant relationship between institutional measures and birth preparedness (P=0.0981) this is in keeping with a randomized study in Nepal which indicated that health education sessions in prenatal clinics, including birth and emergency preparedness counselling provided to pregnant women either alone or with their spouses, produced no change in the frequency of facility-based deliveries.49

5.4 BARRIERS AND FACILITATORS TO BIRTH PREPAREDNESS

From our study, 89.3% respondents have adequately planned for delivery while 10.7% have not made plans for delivery. Among those who have made plans, 23.7% have identified were to deliver while 28% have saved money for delivery, this is in contrast with a study conducted in Adigrat, Ethiopia which showed that 86.9% of the respondents have identified a place of delivery while 83.7% have saved money for delivery. Also, from our study, 22.9% of the respondents have identified a mode of transportation to health care facility during delivery, this is in contrast with the study done in Ethiopia where 40.8% of the respondents identified a mode of transportation to the hospital.26

Our study showed that 61% of the respondents have assistance from their spouses towards birth preparedness; this is in contrast with a study done in Northern Nigeria which reported that males involvemnt in birth preparedness is limited, it reveals that men give high priority to making plans for naming ceremonies rather than critical components of birth preparednesss such as deciding on the place of delivery, skilled assitance and identification of a blood donor. More worrisome is the lack of plans for decision making and savings for obstetrics emergencies.50

CHAPTER SIX

6.1 CONCLUSION

The knowledge of birth preparedness among ANC attendees in Jos North is good as majority of the women have made one or more plans towards safe delivery. This good knowledge and practice can be attributed the fact that majority of the respondents have secondary and tertiary levels of education. However, there was no significant relationship between the knowledge and practice of birth preparedness and measures taken by health institution for safe delivery.

6.2 RECOMMENDATION

Based on findings from the study, we recommend the following actions and hope they contribute in bridging the gap between the knowledge of birth preparedness in Jos North LGA of Plateau state.

- Antenatal care givers should adequately educate pregnant women on the various elements of birth preparedness and complication readiness. Further more, advice on danger signs and what to do when they occur during pregnancy, childbirth and the post-natal period is vital.

- Support from the community is imperative for bith and emergency preparedness. Hence advocacy to involve the commuinty in the design, implementation and evaluation of birth and emergency preparedness service is essential.

- The cost of health services for pregnant women should be subsidized in order to allow all pregnant women to access health care without financial barrier.

REFERENCES

- Vallely L, Ahmed Y, Murray SF. Postpartum maternal morbidity requiring hospital admission in Lusaka, Zambia – a descriptive study. BMC pregnancy in child birth 2005;5:1

- World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, UNICEF, World Bank. Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care – A guide for essential practice. Geneva: WHO 2006.

- Moran AC, Sangli G, Dineen R, Rawlins B, Yamogo M, Baya B. Birth-preparedness for maternal health – findings from Koupla district, Burkina Faso.Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition.2006;24(4):489497.

- JHPIEGO: Monitoring Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness -Tools and Indicators for Maternal and Newborn Health. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg, school of Public Health. Center for communication programs, Family Care International; 2004. Available at:http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnada619.pdf

- JHPIEGO. Improving Safe Motherhood through Shared Responsibility and Collective Action. The Maternal and Neonatal Health Program Accomplishments and Results, Baltimore, Md, USA, 2003.

- JHPIEGO. Birth preparedness and complication readiness: a matrix of shared responsibilities. Baltimore, MD, 2001; 12

- JHPIEGO. Improving safe motherhood through shared responsibility and collective action – The maternal and neonatal health program accomplishments and results, Baltimore, MD, 2002-2003.

- Mihiret H, Mesganaw F. Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness among women in Adigrat Town, North Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2007; 22(1):14-20.

- Adamu YM, Salihu HM, Sathiakumar N, Alexander GR. Maternal mortality in northern Nigeria – a population based study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gyanecol. Reprod. Biol. 2003; 109: 153-159.

- National Demographic and Health Survey, National Population Commission, Abuja, Nigeria; 2004 edition.

- National Population Commission (Nigeria), Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey and ORC/Macro, 2003-2004;51-60.

- Mairiga AG and Saleh W. Maternal mortality at the state specialist hospital Bauchi, Northern Nigeria. East African medical journal. 2009; 86(1): 25-30.

- Ujah LAO, Asien OA, Mutihir JT, Vander jag DJ, Glew RH, Uguru VE. Factors contributing to maternal mortality in Jos, North central Nigeria – A seventeen year review. Afr. Reprod. Health 2005, 9(3): 27-40.

- Abubakar IS, Zoakah AI, Daru HS, Pam IC. Estimating maternal mortality rate using sisterhood methods in Plateau state, Nigeria. Highland medical review journal. 2003; 4:1. 28-34.

- Starrs A.The safe motherhood action agenda: priorities for the next decade – Report on the Safe Motherhood Technical Consultation, Colombo, Sri Lanka.New York, NY: Family Care International; 1997; 94.

- JHPIEGO. Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness -Tools and indicators for maternal and newborn health. Baltimore, JHPIEGO, 2004.

- JHPIEGO. Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness – Tools and indicators for maternal and newborn health. Baltimore, JHPIEGO, 2004.

- .Siddharth A, Vani S, Karishma S, Prabhat KJ, Abdullah HB. Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness among Slum Women in Indore City, India. J Health Popul Nutr 2010; 28:4. 383-391.

- David PU, Andrea BP, Fatuma M Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Mpwapwa district, Tanzania. J Health Research 2012;14:1.

- Hajara Umar Sanda. Media Awareness and Utilization of Antenatal Care Services by Pregnant Women in Kano State – Nigeria. Journal of Social Science Studies.2014; 2:1. 85-111.

- Udofia EA, Obed SA, Calys-Tagoe BNL. Predictors and birth outcomes – An investigation of birth and emergency preparedness among postnatal women at a national referral hospital in Accra, Ghana. East African Journal of Public Health, 2013; 10:3.

- Nepal Ministry of Health and Population, Demographic and Health Survey, Kathmandu, Nepal. New ERA, and Macro International Inc. 2006-2007; M1-25.

- Government of Nepal. Operational guidelines on incentives for safe delivery services. Kathmandu: MoHP; 2005.

- Moke M, Jennifer R, Oona C , Simon C , Mario M and Veronique F. The effectiveness of birth plans in increasing use of skilled care at delivery and postnatal care in rural Tanzania – a cluster randomised trial. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 2013; 13:4. 435-443

- Ibrahim IA, Owoeye GIO, Wagbatsoma V. The Concept of Birth Preparedness in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. Greener Journal of Medical Science 2013; 3:1.

- August F, Pembe AB, Kayombo E, Mbekenga C, Axemo P, Darj E. Birth preparedness and complication readiness a qualitative study among community members in rural Tanzania. Global Health Action. 2015; 8: 26922.

- Muhammed SI, Mu’awiyyah BS, Suleman HI, Sunday A, Shamsuddeen S Y, Abdulhakeem AO, Kabir S. Effect of a behavioural intervention on male involvement in birth preparedness in a rural community in Northern Nigerian. Annals of Nigerian Medicine, 2014; 8:1. 20-27

- Marindo R. The Mira Newako project: Involving men in pregnancy and antenatal care in Zimbabwe – Proceedings of the Reaching Men to Improve Reproductive Health for All International Conference, Dulles, Virginia; 2003. Available from: http://www.zambia.jhuccp.org/igwg/guide/guide.pdf. [Last accessed on 2009 Oct 3].

- Adeleye OA, Chiwuzie J. He does his own and walks away perceptions about male attitudes and practices regarding safe motherhood in Ekiadolor, Southern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2007;11:76-89.

- Feyisetan BJ. Spousal communication and contraceptive use among the Yoruba of Nigeria. Popul Res Policy Rev 2000;19:29-45.

- Orji EO, Adegbenro CO, Moses OO, Amos OT, Olanrenwaju OA. Men’s involvement in safe motherhood. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2007;8:240-6.

- Siddharth A, Vani S, Karishma S, Prabhat K and Abdullah H. Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness among Slum Women in Indore City, India. 2010; 8(4):383-91.

- Ekanem EI, Etuk SJ, Ekanem AD, Ekabua JE. The impact of motorcycle accidents on the obstetric population in Calabar, Nigeria.Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005; 22:2. 164-167.

- Mpembeni RNM, Killewo JZ, Leshabari MT, Massawe SN, Jahn A, Mushi D et al. Use pattern of maternal health services and determinants of skilled care during delivery in southern Tanzania – implications for achievement of MDG-5 targets. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2007;7:29.

- Mihiret H, Mesganaw F. Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness among women in Adigrat Town, North Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2007; 22(1):14-20.

- David PU, Andrea BP, Fatuma M. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Mpwapwa District, Tanzania. Tanzania J of Health Research. 2012; 14:1-7.

- Maternal Neonatal Health: Focused Antenatal Care; planning and providing care during pregnancy. Program brief 2004.

- Wagle RR, Sabroe S, Nielsen BB. Socioeconomic and physical distance to the maternity hospital as predictors for place of delivery – an observation study from Nepal. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 2004; 8:4.

- Hiluf M, and Fantahun M. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Adigrat town, North Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. health dev. 2007, 22(1): 14-20.

- Plateau state, Nigeria http://www.nigeria.unfa.org/plateau.html

- Department of Primary Health Care, Jos North Local Government Area, Plateau state

- Alemu TD, Behailu MG, Marelign TM. Factors Associated with Mens Awareness of Danger Signs of Obstetric Complications and Its Effect on Mens Involvement in Birth Preparedness Practice in Southern Ethiopia, 2014. Advances in Public Health 2015; 2015:9.

- Benjamin AF, Ernest OO, Adenike OA. Sexual dysfunction among female patients of reproductive age in hospital setting in Nigeria, J Health Popul Nutr, 2007; 25(1); 101-106.

- Mihret H and Mesganew F. Birth preparedness and complication readiness among women in Adigrat town, North Ethiopia. J. Health Dev, 2008; 22(1): 8:9

- Mutiso SM, Qureshi Z, Kinuthia J. Birth preparedness among antenatal clients at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. East African Medical Journal Vol. 85 (6) 2008: pp. 275-283.

- Ekabua JE, Ekabua JK, Odusolu P, Agan UT, Ikklaki UC, Etokidem JA. Birth preparedness and complication readiness in Southeastern Nigeria. ISRN obs and gyn doi: 10.5402/2011/560641: volume 2011.

- Anya SE, Hydara A, Jaiteh LE. Antenatal care in the Gambia: Miss opportunity for Information, education and community, BMC oregnancy Childbirth, 2008; 8:9

- Daniel B and Desalegn M. Knowledge of obstetric danger signs among child bearing age women in Goba district, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0508-1: 2015

- Mullany BC, The impact of including husbands in antenatal health education services on maternal health practices in urban Nepal: results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Education Research 2007; 22:166-76.

- Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Galadanci HS, Aliyu MH. Birth preparedness, complication readiness and fathers participation in maternity care in northern Nigerian community. African Journal of Reproductive Health; 2010; 14(1): 21-32