Table of Contents

What is a Plain Abdominal X-ray?

Plain abdominal X-ray is a radiographic assessment of the abdomen without the use of a contrast medium. Contrast abdominal x-ray such as in Barium swallow and Barium Meal and Barium Enema requires the use of Barium as the contrast; in Plain x ray of the abdomen, no contrast is used. There are different types of plain x ray films of the abdomen and all have their indications (i.e. they have their uses for which each is requested). These x ray films report describe the normal features you should find and will be of help when you view the abnormal X-ray findings.

Types of Plain Abdominal X ray

- Supine Abdominal film

- Erect abdomen

- Erect CXR

- Left Lateral Decubitus

- Supine decubitus

- Lateral abdomen

The routine X-ray projection is the supine abdominal film and should include the diaphragms and the symphysis pubis.

Erect Abdomen

This is taken to look for fluid levels and free gas. However, fluid levels are non- specific and free gas (pneumoperitoneum) is better shown on an erect CXR. An erect film is helpful when obstruction is suspected and a diagnosis cannot be made from the supine film.

Erect CXR

An erect CXR should be part of a routine abdominal series because:

- It shows a small pneumoperitoneum more clearly than an erect abdomen. This is because in an erect abdominal film the divergent rays pass obliquely at the level of the diaphragm, which is projected to the top of the film. This part is also often over exposed. In a chest X-ray the top of the diaphragm is almost tangential to the beam.

- An acute abdomen may be complicated by chest pathology: For example:pleural effusions in acute pancreatitis;aspiration pneumonia following prolonged vomiting;basal inflammatory changes with inflammation below the diaphragm;basal atelectasis in post-operative patients and following a pulmonary embolus;heart failure especially in elderly patients.

- Conversely chest pathology may mimic an acute abdomen:Myocardial infarction,Pulmonary embolus,Pericarditis,Lower lobe pneumonia,Pneumothorax,Dissecting aortic aneurysm,Heart failure.

Decubitus views

These may be useful instead of an erect film if the patient is unfit to stand. A left lateral decubitus view is taken with the patient lying on the left side. The film is placed behind the patient and the tube aimed to the centre of the abdomen. This shows fluid levels and small amounts of free air will be seen between the liver and the diaphragm. If the patient is unable to turn onto the side, a supine decubitus film may (rarely) be necessary. It will show free air but is less useful. In babies with imperforate anus, a prone decubitus film with the buttocks elevated is sometimes taken. This however may be misleading and many centres are now using ultrasound to show the level of rectal atresia.

Lateral abdomen

This is seldom necessary but may occasionally be useful for suspected aortic aneurysm (if ultrasound is not immediately available).

An abdominal X-ray is seldom helpful in the diagnosis of chronic abdominal pain. It is of no help in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis or certain other acute conditions such as ruptured ectopic pregnancy. A normal abdominal X-ray does not exclude serious pathology and is often unhelpful. Bearing this in mind abdominal X-ray should be reserved for patients in whom it is likely to be helpful in diagnosis.

Indications for Plain Abdominal X-ray

- suspected intestinal perforation

- suspected intestinal obstruction

- renal colic in suspected cases of calculus

- foreign body

Plain abdominal x ray films are NOT indicated for the following (Contra-Indications)

- non-specific abdominal pain

- gastro-enteritis

- constipation

- acute appendicitis

- urinary retention

- pancreatitis

- acute urinary tract infection

- diarrhoea

- acute peptic ulceration

- haematemesis/malaena

- biliary disease

Normal Plain abdominal X Ray Features

When assessing an abdominal film, a study of three areas will cover the majority of abnormal findings: bowel gas pattern, areas of calcification, and skeletal abnormalities.

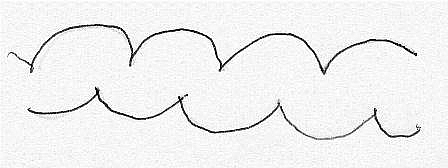

- The small bowel lies centrally. There should be no more than 3 short fluid levels on an erect film. There should only be small amounts of gas in the small bowel. After being swallowed air reaches the colon within 30 minutes. The jejunum is recognised by valvulae conniventes, folds which traverse the full width of the bowel. The distal ileum is smoother in appearance.

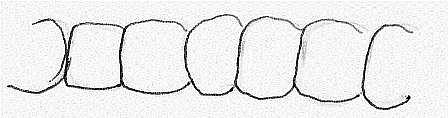

- The large bowel lies peripherally. There may be longer fluid levels and the maximum diameter is variable. The large bowel often contains faeces & has a speckled appearance due to gas trapped in the faeces. The haustra may be outlined by gas. It is quite common to see gas outlining much of the large bowel normally. The haustra can be recognised by the fact that they do not cross the full width of the bowel and they are not regular.

- The bladder may be seen as a soft tissue density arising from the pelvic floor.

- The stomach is normally outlined with air below the left hemidiaphragm.

- Calcifications may be seen that are not significant

Phleboliths in the pelvis these may mimic lower ureteric stones but are more rounded in appearance. Often multiple.

Mesenteric nodes. These are often confused with renal or ureteric calculi but they are mobile and move with posture.

Costal cartilages. These may cast confusing shadows in the upper abdomen and may be confused with renal calculi. They can easily be distinguished by taking an oblique film.

Prostate. Calcification is often seen in the prostate and is a normal finding. It should not be confused with a bladder calculus. It lies below the bladder, centrally.

Seminal Vesicles. These occasionally calcify. They are serpiginous in appearance, lying behind the bladder. Calcification is commoner in diabetic patients. - Fat lines:It is only because of the fat surrounding the internal solid organs that they are visible. The renal outlines can usually be seen, as can the psoas shadows. A fat line lying adjacent to the parietal layer of peritoneum in the flanks can sometimes be seen. This is called the properitoneal fat line