Table of Contents

- WHO ARE CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVISTS?

- MUHAMMAD ALI JINNAH

- HAROLD BELAFONTE Jr.

- MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

- BIRTH AND EARLY LIFE

- MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT OF 1955

- THE ATLANTA SIT-INS OF 1960

- THE ALBANY CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT OF 1961

- BIRMINGHAM CAMPAIGN OF 1963

- MARCH ON WASHINGTON FOR JOBS AND FREEDOM 1963

- CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964

- TITLES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964

- VOTING RIGHTS;

- INJUNCTIVE RELIEF PERTAINING DISCRIMINATION IN PLACES OF PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION;

- DESEGREGATION OF PUBLIC PLACES;

- DESEGREGATION OF PUBLIC EDUCATION;

- COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS;

- NON DISCRIMINATION IN FEDERALLY ASSISTED PROGRAMS

- EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES;

- REGISTRATION AND VOTING STATISTICS

- INTERVENTION AND PROCEDURE AFTER REMOVAL IN CIVIL RIGHTS CASES

- ESTABLISHMENT OF COMMUNITY RELATIONS SERVICE

- MISCELLANEOUS;

- TITLES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964

- SELMA TO MONTGOMERY MARCH

- BLOODY SUNDAY

- KING OPPOSES THE VIETNAM WAR

- Dr. KING’S ASSASINATION

WHO ARE CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVISTS?

Civil rights are the rights of people to social and political equality. Civil rights activists are leaders of movements especially political movements rooting for the rights of people and equality for everyone especially those in minority groups. Civil rights activists can also be called civil rights leaders. Throughout the course of history, there have been individuals that have contributed greatly to the promotion of civil rights movements around the globe. The following are civil rights activists who fought for different rights of people from different parts of the world. Some of these people were banned from their countries, arrested, or even killed but they kept on and kept pushing and it can be said that there are rights enjoyed today that wouldn’t have been enjoyed if these people did not fight tirelessly. Most are not even alive to see the results of their fights but they would forever be honored by the world for their bravery, courage, and resilience. Some of these civil rights leaders are;

MUHAMMAD ALI JINNAH

BIRTH AND EARLY CHILDHOOD

This Civil rights leader was born as Mohomedali Jinnahbhai on the 25th day of December 1876 in Sindh, Pakistan, in Bombay, British India. He was the second of six children from a wealthy background. He was a born Muslim, with the Gujarati Khosha Shia Muslim group. The language of his parents was the Gujarati language. Mohamed, however, didn’t speak his native language well (Gujarati), he spoke more of English and Kuchi. He attended Cathedral and John Connon school. He left Bombay in 1892 to London for an apprenticeship with his father’s business associate, Sir Leigh Croft. He, however, resigned from the apprenticeship not long after he had arrived, he enrolled in law school and this decision was not taken very lightly by his father who before his departure had given him money that should have lasted him three years. He, unmoved by his father’s anger continued on his chosen path. He enrolled into Lincoln’s Inn.

EDUCATION

He started his pupilage which was part of the process of being a lawyer in those days. It entailed working as an apprentice with an already established lawyer and he gained experience and knowledge while following the man and also doing his own studies alongside. He became fascinated by the British liberalism of the 19th century and eventually became a follower of the Parsi British Indian political leaders Dadabhai Naroji and Sir Pherozeshah Mehta. He was generally interested in the British way of life which not only shaped his political beliefs but even his way of life and it also influenced his decision to be a civil rights activist.

His style of dressing also changed and one thing he was known for was that he was never shabbily dressed. He had a signature hat which was known as the Jinnah cap because of how often he wore it. In 1985, he was called to the bar and was known as the youngest Indian to be called to bar at 19. He returned to Bombay and started his practice when he was 20. He worked from 1897 to 1900 not so many cases but the brake light for his career came when John Molesworth, the then advocate general of Bombay called him to work with him at his chambers to which he agreed. After six months of working there as a temporary staff/intern, he was offered a permanent position for 1,500 rupees per month which was a lot of money back then, but Mohammed declined and said he wanted to earn that amount every day. The Caucus case of 1908 which he won at the behest of Sir Pherozeshah Mehta was what led him to prominence and it was the talk of the town for a while.

ACTIVISM

Jinnah was known as an active trade unionist and he was even elected president of the seventy-member All India Postal staff in 1925 where he fought for their fair rights and got good deals to improve their living conditions. Many Indians all over the world started to move to gain their independence from the British government which led to the formation of the India National congress of 1885. Jinnah first attended their 20th meeting in 1904 and moved for Hindus and Muslims to coexist and work together to secure India’s independence which would benefit both parties immensely. Jinnah however was opposed by many for this as the Hindus and Muslims did not always see eye to eye on political issues. In 1913, he went to Britain with a Hindu representative, Gokhale to discuss the interests of the congress. Jinnah worked tirelessly to bring the congress and the Muslim league together.

Jinnah became president of the Muslim league in 1916, Jinnah became the president of the Muslim League and succeeded in leading the two parties to sign the Lucknow Pact. Although the pact was not fully enacted, it went a long way in fostering a relationship between congress and the league. Jinnah married Rattanbai Petit in 1918, he was 24 years older than her and she was Hindu. This caused a lot of controversies and even got her exonerated from her family because she decided to convert to be a Muslim and marry Jinnah. The couple welcomed a baby girl, Dina, who would be their only child in 1919. His wife died 10 years later and Jinnah’s sister, Fatimah took over caring for him and Dinah.

Jinnah did not agree well with Mahatma Gandhi who he considered a Political anarchist. India however, was more taken to Gandhi because he was a more traditional man than Jinnah from his dressing, his lifestyle, and even his language. Eventually, the congress endorsed Gandhi’s proposal over Jinnah’s which led to him resigning from all his positions in the Congress but he remained in the league actively.

Jinnah moved back to England and was fully involved in legislative affairs and the parliament and was even offered Knighthood which he declined. There are various reports from biographers who have different stories of what happened while Jinnah was in England, none of which have been confirmed true or false. Jinnah suffered a chronic lung disease after his sister, Fatima moved to England with him in 1931. She was his closest advisor and friend as she cared for him and traveled with him. His daughter Dina had her education in both England and India but she, however, was exonerated by her father when she decided to marry an Indian Christian gentleman, Neville Wadia who was from a very prominent and wealthy Parsi family. When Jinnah tried to dissuade his daughter from marrying outside their religion, she reminded him of how he married her mother who was not of the same religion as him. Dina stopped coming to see her father after she married Neville and didn’t even come to Pakistan until during his burial.

On the 3rd of September,1939, the then British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, announced that Britain was going to war with Nazi Germany during the second world war. And without consulting the Indian leaders, he announced that India will be fighting alongside Britain. In this period, Jinnah and the Muslim league gained favor with the British, and they became recognized as the voice of Muslim Indians. Although the league did not support the dragging of India into the war, they didn’t try to stop the British. On 2nd March of 1940, a resolution, the Lahore Resolution was passed which would help the Indian Muslims and British coexist and protect the rights of Muslims, even those who were in regions where they were minorities. They were making a move for the secession of the Muslims to have their own state; Pakistan in the Indus Valley.

The league believed that the others were not after their interests of the Muslims. Jinnah was so passionate about his desire to get the Muslims free from association with the Hindus and to practice their religion without persecution. Finally, on the third of June, 1947, after a lot of ruckus and drama, Pakistan was created and on the 14th of August, Pakistan gained independence with Jinnah as its Governor-General. He put everything on the line and fought for what he believed in.

DEATH

Jinnah however, battled with Tuberculosis for almost 30 years and his lifestyle did not help either as it was stated that he smoked about 30 to 50 cigarettes a day and neglected medication. It got worse and he was soon diagnosed with lung cancer. He passed on on 11th September 1948 in his home in Karachi and was buried the next day. All executive programs were canceled that day to honor him and his memory and his funeral had over a million people in attendance. He died at age 71 and was buried at Mazar-e-Quaid in Karachi. He is known as the founder and first governor-general of Pakistan and also known as Quaid-i-Azam(great leader) and his birthday is a public holiday in Pakistan. He was a great civil rights activist that is still very much celebrated especially among the Pakistani Muslims.

HAROLD BELAFONTE Jr.

BIRTH AND EARLY LIFE

Known worldwide for hit songs such as “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O), African-American civil rights leader and activist, Harold George Belafonte Jr. was born on March 1, 1927, in New York City to Caribbean immigrants. When Harry was a young boy, his father, who left the family, served as a cook on merchant ships. His mother was a dressmaker and a house cleaner. Harry spent much of his early years in Jamaica, his mother’s homeland. Witnessing the oppression of black people by the English authorities left a lasting impression on the young Belafonte. In 1940, he returned to New York to live with his struggling mother and attended George Washington High School. Eventually dropping out, he enlisted in the Navy in 1944.

After his discharge, he returned to New York once again and was working as a janitor’s assistant when he was given two tickets as a gratuity to see the American Negro Theater (AMT). Mesmerized by the performance, he fell in love with the art form and volunteered to work as a stagehand. He also met Sidney Poitier. He eventually decided to become an actor and took classes in acting at the Dramatic Workshop of The New School run by influential German director Erwin Piscator alongside Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Walter Matthau, Bea Arthur, and Sidney Poitier, while also doing performances with the American Negro Theater. Along with He soon began acting. He started his career in music as a club singer to pay for his acting. Eventually, he caught the eye of music agent Monte Kay and was offered the opportunity to perform at a Royal Roost jazz club. Backed by the Charlie Parker band, which included talented musicians such as Max Roach, Charlie Davies, as well as Charlie Parker himself, Belafonte became a popular act at the club and eventually landed his first recording deal with the club’s record label in 1949.

At first, he was a pop singer, but in the early 50s, he developed a keen interest in folk music, learning through the Library of Congress’ American folk songs archives. He would make his debut shortly afterward at the legendary jazz club The Village Vanguard with a friend and guitarist Millard Thomas. In 1953, he signed a contract with RCA Victor, and he worked regularly and released songs under the label until 1974. His breakthrough album Calypso (1956) introduced audiences to calypso music, and Belafonte was dubbed the “King of Calypso”. During this time he made his Broadway debut, appearing in the musical John Murray Anderson’s Almanac (1953–54); for his performance, he won a Tony award for supporting actor. Later in the decade, he starred on the stage in 3 for Tonight and Belafonte at the Palace.

In 1953 Belafonte made his first public appearance in the movie Bright Road, playing the part of a school principal. The following year he was the male lead (but did not sing) in the musical Carmen Jones; his costar was Dorothy Dandridge. The film was a huge success, and it led to a starring role in the film Island in the Sun (1957), which also featured Dandridge. He also produced the film Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), in which he was part of the cast. He also starred in the TV special Tonight with Belafonte (1959), a show of African American music he went on to win an Emmy Award for his work on the show.

Belafonte then took a break from acting to focus on other interests. In the 60s, he became the first African- American TV producer, and over the course of his career, he served in that position on several productions. During this time Belafonte continued to record, and his notable albums include Swing Dat Hammer (1960), for which he received a Grammy Award for best folk performance.

ACTIVISM

As a civil rights activist, Harry’s political beliefs were strongly inspired by his mentor, actor, and civil rights activist Paul Robeson, as well as a writer and activist W.E.B. Du Bois. He supported the Civil Rights Movement in the 50s and 60s and was also one of Martin Luther King’s confidants. He provided backing financially for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and took part in numerous protests and rallies. He helped organize the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington, where MLK gave his famous “I Have A Dream” speech on the steps on the Lincoln Memorial. Belafonte also began supporting new African artists, such as Miriam Makeba (also known as “Mama Africa”), whom he met in 1958. Together they won a Grammy for Best Folk Recording for their album An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba.

In 1985 Belafonte helped organize the Grammy award-winning song “We Are The World”, written by Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie, as an effort to raise funds for the relief of those suffering from famine in Ethiopia. In 1987, he received an appointment as a goodwill ambassador to UNICEF. He campaigned to end apartheid in South Africa, and his last studio album, Paradise in Gazankulu, released in 1988, contains ten protest songs to that cause. In the same year he, as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador attended a symposium in Harare, Zimbabwe, to concentrate attention on child survival and development in Southern African countries. As part of the symposium, he performed a concert, which was recorded by a video crew and released as a one-minute video called the Global Carnival. From the 1980s to the early 2000s, he did more stage performances and concerts that were completely sold out. His last noted performance/concert was the Atlanta Concert which was a benefit. In 2003, he fell sick and even had to cancel some shows and officially announced on the 25th of October,2003 that he has retired from performing. It is very important to note that he was a very good friend of Martin Luther King Jr.

He received a lot of awards and was recognized and given honorary awards and even degrees for his impact through his movies. Some of the movies are;

- Carmen Jones

- Beat Street

- Island In The Sun

- Kansas city

- Buck And The Preacher

- Bright Road

- Porgy And Bess

- White Man’s Burden

He married Marguerite Byrd in 1948 and had two daughters, Adrienne and Shari. They got divorced in 1957, nine years later. Harry in March of 1957, got married again to Julie Robinson, a former dancer. This union produced two children, David and Gina. They however got divorced in 2004 after about 47 years of being married. Four years later in 2008, Harry married again for the third time. He married Pamela Frank, a photographer. And he had five grandchildren; Rachel, Brian, Maria, Sarafina, and Addeus.

Harry publicly opposed the George Bush administration he referred to it in an interview as arrogant, morally bankrupt, and ignorant. Harry clocked 94 years on 1st March 2021 and he’s still very agile and active and still featuring in movies and songs. He is one person who can never be forgotten as he was a strong part of the anti-apartheid movement.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

BIRTH AND EARLY LIFE

Born as Michael King junior on 15th January 1959, to his Reverend Michael King sr. and Alberta King who were black civil rights activists and were part of the early civil rights movement. He was the second of three children. His father, a serious civil rights leader for blacks was a pastor who took over from his grandfather after he died, because of this, the church sent him on many missions to different parts of the world on assignment. He visited Berlin, where he discovered a lot of things about Martin Luther, the German composer, and monk, he saw his works and his history and was greatly influenced by it and decided to change his name and his son’s name to Martin Luther after the composer. His son’s name was changed when he was 28 and his certificate was altered to read Martin Luther King jr.

King was a very bright and loving child growing up with his siblings. He was brought up in a Christian home and exhibited good virtues and behavior. As a child, he made friends with a white kid with who he played and was friendly until the boy’s parents stopped their son from playing with Martin and stated to him that he was colored and their son was white before severing ties with their son. At this point, Martin’s parents told him about the struggle of black people and racism. His parents however told him to not hate anyone and love everyone around him just as a good Christian should be. He went to church regularly with his parents and sang in the choir. It was recorded that he was a very good singer. He sang while his mother played the piano. He eventually started playing the piano and violin just like his mother. He read and memorized verses from the Bible. In May of 1941, King who was supposed to be reading for school, snuck out to watch a parade and upon reaching home, he found out that his grandmother had died of a heart attack while he was away. He thought that was God’s way of punishing him for sneaking out to the parade instead of reading at home so he decided to jump off a window in his house. He survived and his father told him God wasn’t punishing him by taking his grandmother. This just goes on to show how much of a good and innocent kid King was.

King was enrolled in Brooker T. Washington school which was the only school for African-American kids in 1942 and he also worked as an assistant manager of the local newspaper delivery station, The Atlanta Journal at age 13. In school, History and English were his favorite courses. Although he liked English, he didn’t like the spelling aspect of it. So, he and his elder sister, Christine helped each other with their school work. She helped him with his spellings and he helped her with her maths. King ended up taking English and Sociology as his majors. King joined the debate team because he was good at public speaking and he had a very wide vocabulary. King was one of the cool kids in his days among his peers because he took a liking to fashion and was known for frequently wearing leather shoes and tweed suits. This earned him the name ‘Tweedie among his friends.

In 1944 at just 15, he delivered his first speech in his junior year of high school and was declared the winner of the competition. In that same year, an all-male black college took in students from junior high schools who passed the examination to enroll in the school, The Morehouse College. His father and grandfather had attended this school. The school was open to junior students which was not part of their policy initially but because this was during World War II and a lot of the black boys were enlisted in the army so the college was low on students and opened up to the junior ones. King passed the examination and got enrolled in the school for its autumn semester, But before the semester began, during the summer before that, King was sent to a Tobacco farm in Connecticut along with some of the other students of the Morehouse college to work and be able to pay for their tuition and other bills while they’re in the college.

King stated that he’d never seen such a place before as that was the first time he traveled out of the south which was a very racist area. He said there wasn’t any discrimination and racism in Connecticut and that the white people there were in fact nice. He found it pleasing that he could sit where he wanted, eat anywhere, and even attended the same churches as the whites under the same roof. While at Morehouse College, King took a major in Sociology, and his final year in the college, he decided to go into ministry at eighteen under the spiritual mentorship of a baptist minister, Benjamin Mays. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Sociology in 1948 at nineteen.

King went on to enroll in the Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennysylvania with his father’s support. His father arranged for him to work with an old friend, J.Pius Barbour, a pastor who pastored Calvary Baptist Church in Chester, Pennysylvania close to Kings’ Theological school. He was exceptional and was elected president of the student body. While in school, he met and got into a relationship with a white German girl whom he planned to marry but he broke up with her after six months because his mother refused the marriage and also his friends too. He graduated in 1951 and went on to Boston University and enrolled to study Systematic Theology. He worked with Reverend William Hunter Hunter of the Twelfth Baptist Church, an old friend of his father. King also attended philosophy classes at Havard in 1952 and 1953 as an audit student. He married Corretta Scott who he met through a mutual friend while he was still studying at the Boston University and married her on the 18th June 1953. King and Coretta had four children;

- Yolanda King (1955-2007)

- Martin Luther King III (1957)

- Dexter Scott King (1961)

- Bernice King (1963)

In 1954, at age 25, he was appointed pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and got his Ph.D. on the 5th of June, 1955.

MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT OF 1955

In March of 1955, Claudette Colvin a fifteen-year-old African-American schoolgirl was arrested because she refused to leave her seat and have a white man seat in her place which was violating the Jim Crow Laws but because she was a minor. The case was closed after that. Not so long later, on the 1st of December in that same year, another case came up when a black woman, Rosa Parks, a seamstress on her way back from work that evening refuses to give up her seat in a bus for a white man and she got arrested due to this. This incident led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott which was led by E.D Nixon, an African-American civil rights activist and the president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Jo Ann Robinson alongside King. King was skeptical about taking the lead on this case when the other ministers suggested he does it because he was a newly ordained minister and was best for the job. this boycott lasted for 381 days. Nixon and other black civil rights activists used this situation as a springboard to take up the case of the bus segregation policy. Jo shared around fliers for the boycott because most of the bus drivers were African-Americans. The boycott was planned for buses on the 5th of December. They planned that the boycott will go on as long as possible to get the government’s attention. And while the boycott took place, King and the others bought cars and wagons for people to move around town with temporarily. This situation got so tensed that King’s house got bombed on the 30th of January, 1956, thankfully with no casualties. While the boycott was going on, a case was opened concerning it in court, and on the 13th of November, 1956, a ruling was passed in their favor and the buses in Montgomery were integrated, the ruling prohibited any form of racial segregation in the buses. The boycott officially ended on the 20th of December, 1956. This boycott was what brought Martin Luther King out as a human rights activist.

He moved back to Atlanta in 1959 and pastored the Ebenezer Baptist Church with his father until his death.

THE ATLANTA SIT-INS OF 1960

When King moved back to Atlanta, the Governor, Ernest Vandiver was not happy about King’s return and publicly expressed his displeasure on his return. He said crime was always at a high rate wherever the king went. He put King under high surveillance and on the 4th of May,1960, King was arrested while he was driving his writer friend, Lillian Smith to a university. He was arrested for not having a license to drive. It wasn’t that he didn’t have a license, he just didn’t have a license by the state of Georgia, but he still had a valid license from Alabama where he was coming from. He was released and paid a fine, but unknown to him, the agreement his lawyer had with the state to secure his release was that there will be a probationary sentence attached to the fine he paid to be released.

In March of that year, the Atlanta Student Movement decided to stage a protest for the segregation that was taking place in businesses and public places. They organized sit-ins from March and kept going until August where they decided to ask King to join them in their October sit-in. King obliged and it took place on the 19th of October at the largest departmental store there. This particular sit-in was not just aimed at the segregation going on, but also to address the way the candidates of the 1960 presidential election ignored all about civil rights. A lot of people got arrested that day during the sit-in and King was one of them. These people however were released within the next few days and King was still being detained. King was taken to court and reference was made to his probationary sentence and he was sentenced to four months in prison with hard labor on the 25th of O October. He was transferred to a maximum-security prison before the next day. When the news of King’s sentence got out, it gained the attention of the public.

There were attempts to get him out through pleas by the black leaders as they feared for his safety in the prison because most of the prisoners were white criminals who opposed his activism. His friend, before the sit-in, Nixon who was a presidential candidate declined to make a statement to help in securing the release of King. His opponent, however, John F Kennedy placed a direct call to the governor, and even went on to ask other people for help and two days later, King was released. As a show of appreciation from King’s father for helping to secure the release of his son, he endorsed and supported J.F Kennedy’s campaign publicly. Kennedy won the election, only by a few votes.

After the sit-in that had King arrested, a thirty-day truce was arranged to negotiate the segregation policy. These negotiation moves failed and segregation was soon back in full swing and this caused the blacks to resume sit-ins and boycotts full time. This action by the African-American members of the community-led to an agreement that the schools would be desegregated and that the lunch counters will also be desegregated. But because this was not what the African-Americans wanted, they were not happy and got hostile towards the elders of the black community until King gave them a speech on the effects of disunity amongst them which helped calm them to an extent.

THE ALBANY CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT OF 1961

This was started on the 17th of November,1961, it was a desegregation movement in Albany, Georgia. It was formed by the National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Negro Voters League, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led by King and other black leaders. When King and the SCLC joined the movement, it gained more publicity as King already had a reputation for being a frontline in activist movements in the city. The protest was initially aimed at stopping segregation of all forms in the city, from segregation in transport facilities to discrimination in schools and also to work on the release of people arrested during desegregation rallies and protests. The leaders of the protests were Williams G. Anderson, a local doctor who was made the president, and Slater King, a realtor who was the vice president.

The protest was mostly nonviolent and the methods used in achieving their aims were sit-in, boycotts, litigations, mass demonstrations, and jail-ins. This movement however was countered by mass arrests of protesters and by December of that year, well over 500 protesters were arrested. When King came on the 15th December at the request of Anderson, the leader of the movement, and addressed some of the protestors and he went out with them to protest the next day, but he got arrested alongside Anderson and Ralph Abernathy. His arrest got the attention of a lot of people in the black community. King refused bail while in jail unless the city met the demands of the people. They agreed with King that if he leaves, the city would meet the demands of the people and would release the jailed protesters. King left but the city, however, did not hold up their own part of the bargain. The protests still went on and people were still being arrested. Even those formerly arrested were not released.

King came back in July of 1962 Ralph and was arrested on charges of parading without a permit in December of 1961. They were given the option of forty-five days in jail or a fine of one hundred and seventy-eight dollars ($178) and they chose to not pay the fine and stay in jail. King’s arrest turned up the rates of protests in the city and more people were participating. On the 12th of July, the police chief, Laurie Prichett told the men that they were free to go and their bail had been paid by an “unidentified black man” who turned out to be Billy Graham. On the 10th of August, 1961, King decided to leave Albany which signified his withdrawal from the Albany movement. The Albany movement is known as one of King’s few failed activist movements as no major victory was conceded during this movement and the demands of the movement were not met. King however later stated that the failed Albany movement helped in planning and strategizing for other protests and movements.

BIRMINGHAM CAMPAIGN OF 1963

In April of 1963, King along with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Alabama Christian Movement For Human Rights (ACMHR) joined forces to fight against economic injustice and racial segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. Their approach was a non-violent one and they decide to put pressure on the state through its merchants during the second-biggest shopping season, Easter. The protest was nonviolent and it consisted of sit-ins in churches and libraries, boycotts of merchants, march at city halls and there was a march held at the county building for voter registration. Hundreds of people were arrested during this protest. This was King’s aim anyway, to have so many protesters arrested so that it will be a crisis and the city would have no choice but to look into the matter and begin negotiations. This however did not go so long in getting them what they wanted.

The city government got a court injunction against the protesters which was supposed to stop them from continuing with their protests but the black leaders had a meeting, deliberated, and refused to comply with this court order. They said they would not agree to an undemocratic order that took away their rights from them especially as their protests have been nonviolent so far. They kept on with their protest and funding was a challenge for them but they still kept going nonetheless. On the 12th of April, King was arrested and put in solitary confinement for violating the court injunction passed. He was not even allowed to contact his wife, Coretta who had just delivered their fourth child in Atlanta and was trying to get in touch with him, she called the president who was able to intervene in the matter and the police let her speak with her husband. King was released on the 20th of April on bail.

After King’s arrest, SCLC strategist, James Luther Bevelcame up with a plan to involve children and young African-Americans in the protests. On the 2nd of May, thousands of African-American students came out to march in Birmingham and hundreds were arrested that day and also on the next day too. The police and fire department were trying to bring a stop to the protests. They went violent on these protesters including the children who were involved in the protests. They were led by Eugene Bull Connor, the commissioner for public safety in Birmingham then who ordered them to use force to stop the demonstrations. They used high-pressure fire hoses, clubs, and even police dogs on these protesters without even excluding the children. The images of children being maltreated and manhandled by the police on the media caused so much uproar and outrage within the city and this even made some whites start advocating for the rights of the blacks.

Because of the pressure that was coming at the city’s government and economy, the city decided to gather the black leaders and negotiate with them. The negotiation was led by Burke Marshall on behalf of the city’s attorney general. Marshall urged the black leaders to halt the protests, come to an agreement and compromise to the partial benefit of the blacks and after all, tension dies down, more negotiations can take place and Eugene Bull Connor lost his job too. King agreed to this and declared a moratorium on the protests. They all came to an agreement on the 10th of May with some conditions like;

- Removal of “whites only” and “blacks only” signs in public bathrooms and facilities and also on drinking fountains.

- Upgrade of the employment of the blacks

- Desegregating public places

- Release of every jailed protester unconditionally

This agreement is known as The Birmingham Agreement Truce. Some of the racists in the city were not happy with this and went violent on the blacks. The hotel King was staying at was almost bombed, KIng’s brother’s house was bombed and a troop of 3,000 soldiers was sent to Birmingham to keep things in check. However, on the 15th of September, Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was bombed and four little girls died in the explosion. This however did not deter the blacks from still fighting for their rights. Although King and the SCLC were criticized for bringing children into this movement, it was a successful campaign and tangible results were achieved.

MARCH ON WASHINGTON FOR JOBS AND FREEDOM 1963

- This is the march that took place on 28th August 1963 in Washington for jobs and freedom and protests racial discrimination. The president, John F. Kennedy initially refused the march because he thought it would end in violence. 1963 was the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation which was passed by Abraham Lincoln with not so much impact even a hundred years after it was passed. Blacks were no longer slaves but they weren’t entirely free either as they had to deal with segregation and low living standards, bad jobs, low standard schools amongst others. This was one of the reasons why the protest was held at the Lincoln Memorial.

Lincoln memorial where the Washington march took place

Randolph Philip the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters organized this whole movement by writing to and getting in touch with top black leaders and mobilizing everything that will be needed for the march. He wrote a letter to King telling him of his plan for the March. The demands for this march were;

- Two dollars ($2) minimum wage payment for all black workers

- Desegregation of all public schools

- Prohibition of all forms of racial discrimination in regards to employment

- Protection of civil rights activists from police brutality

- Protection of blacks generally from discrimination and segregation

- Self-government for Washington D.C

- Fair civil rights legislation

This March was not supported by all blacks, however. Some black individuals and bodies frowned at it including Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam. Although Malcolm X eventually attended the March. There were many people who gave speeches and performances at the March like Roy Wilkins, John Lewis, Whitney Young, Bayard Rustin among others but King’s speech stood out the most at the event. His speech was delivered towards the end of the march and it moved the population of the over 200,000 people that were in attendance. His speech was titled “I Have A Dream”. His speech was the highlight of the event that day and is one of the most popular speeches ever delivered in history. George Raveling, a 26-year-old security volunteer at the event asked King for the original typewritten speech and even his handwritten notes with the speech and King gave it to him. He had an offer to sell it for $3,000 then but he declined to say he didn’t have plans on selling it. Below is the full speech delivered by Mr. King at the march;

I HAVE A DREAM BY MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

“I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice.

It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free.

One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.

One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.

One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.

And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense, we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check.

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.

This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable Rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.

Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.

We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation.

And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now.

This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy.

Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice.

Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment.

This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality.

Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning.

And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

And there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights.

The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people, who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice; In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds.

Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline.

We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence.

Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.

The marvelous new militancy that has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have realized that their destiny is tied up with their our destiny.

And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead.

We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights,

When will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality.

We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one.

We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their self-hood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: “For Whites Only.”We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations.

Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells.

And some of you have come from areas where your quest, quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality.

You have been the veterans of creative suffering.

Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.

It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification. One day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope, and this is the faith that I go back to the South with.

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.

With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.

With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day, this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning:

My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing, land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride,

From every mountainside, let freedom ring!And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.But not only that,

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men, and white men, Jews, and Gentiles, Protestants, and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual,

Free at last!

Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964

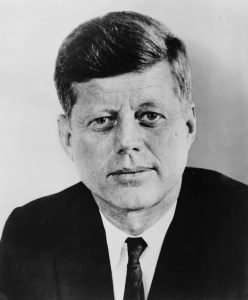

Prior to the Washington march, the president, John F. Kennedy had introduced a civil rights legislation that had not been passed. This new act that he proposed would address all the issues that the blacks had been advocating for since emancipation. The Washington march was a driving force to the government passing this act. The president was however assassinated before he could pass the civil rights act to the law while riding in a motorcade alongside his wife on November, 22nd 1963.

Picture of president John Kennedy.

After his assassination, the vice president, Lyndon Baines Johnson with the help of Roy Wilkins and Clarence Mitchel pushed the bill. On the 10th of February 1964, the united states house of representatives passed the bill. After a filibuster in the house of representatives, it was finally signed into law by the new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson on the 2nd of July, 1964. President Lyndon said that the passing of the law would be the best way to honor the memory of the late president Kennedy who put in a lot to see the bill being passed into law. This act brought an end to the use and application of the Jim Crow Law.

TITLES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964

There were a total of eleven parts or titles to the Civil rights act of 1964. These parts were;

-

VOTING RIGHTS;

This segment of the act disallowed racism and segregation of any sort in voting. It however was not really all-encompassing as there were still literacy tests that voters had to pass before being allowed to vote. So even though it allowed blacks to vote, there were still barriers they had to get through before being eligible to vote.

-

INJUNCTIVE RELIEF PERTAINING DISCRIMINATION IN PLACES OF PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION;

This act abolished segregation or discrimination in public spaces based on race, religion, color, background, class, or any other discrimination factor. Public places were open to all people except privately owned property. Hotels, bars, clubs, motels, were all opened to everyone.

-

DESEGREGATION OF PUBLIC PLACES;

This allowed everyone accesses to public facilities like buses, toilets, etc

-

DESEGREGATION OF PUBLIC EDUCATION;

This segment allowed people of all color access to schools regardless of color, nationality, religion, or race. All schools were open to everyone.

-

COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS;

This part buttressed the part of civil rights of all people. It prohibits infringement on anyone’s rights.

-

NON DISCRIMINATION IN FEDERALLY ASSISTED PROGRAMS

-

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITIES;

This part prohibits segregation or discrimination when it comes to giving jobs to people. There will be equal job opportunities and equal pay.

-

REGISTRATION AND VOTING STATISTICS

Voting registration and data collection must only be in areas approved by the commission of civil rights.

-

INTERVENTION AND PROCEDURE AFTER REMOVAL IN CIVIL RIGHTS CASES

-

ESTABLISHMENT OF COMMUNITY RELATIONS SERVICE

The community relations service was established to deal with community disputes regarding discrimination

-

MISCELLANEOUS;

This part gives accused criminals rights to a jury trial in parts two, three, four, five, six, and seven. If they are found guilty, they are to go to jail for a maximum of 6 months or pay a fine of $1,000 maximum.

SELMA TO MONTGOMERY MARCH

In December of 1964, King and the SCLC collaborated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Selma, Alabama to protest voting registration procedures for black voters. A protest was organized and a march was scheduled from Selma to Montgomery which was roughly a 54-mile distance with over 25,000 thousand people in attendance. The March, however, was disrupted and turned violent by the local white vigilante troops. They still went on regardless and the March went on for three days. They went round the clock and kept marching without stopping. Even though the civil rights act of 1964 was passed and voting rights were given to everyone without racism or discrimination, the whites in the southern state of Alabama violently kicked against it and opposed it. It was still hard for the blacks to register for voting. Voter registration was a very cumbersome process open only two days in a month for people to register coupled with the fact that only blacks who were learned and educated could even get their registration done because of the four-page complicated form that had to be filled for the literacy tests. So out of thousands of black in the city, only roughly 2 percent of the people were successfully registered. King alongside the other civil rights leaders encouraged the people to fight for their voting rights. When the protests first began, it met opposition by a lot of the white southerners and on the 18th of February 1965, during one of the demonstrations in Perry, a county near Selma, one of the demonstrators, Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot when the demonstration got violent on peaceful protesters during a nighttime protest.

Jimmie died a few days later due to his injury in Selma. The leaders of the movement decided to bring the injustice of his death to the knowledge of the general public and raise awareness on the alarming increase of violence on peaceful protesters. George Wallace, the governor of Alabama at that time prohibited the March that was being organized and he told the troopers that he’s giving them an order to stop the protesters by every means necessary on the 6th of March, 1965.

BLOODY SUNDAY

King decided to hold the March on the 7th of March regardless of what the governor said. He and the remaining black leaders decided to arrange the March. Although King’s father had asked him to preach on that Sunday and postpone the March till the following day but King decided against it in order to not discourage those who had traveled just to take part in the protest. The protesters converged at the Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church and were told to be nonviolent in their protest and were told to only sit and pray if they were stopped or even arrested or teargassed. They were encouraged to remain peaceful through it all. The protest was led by Hosea Williams one of the SCLC lieutenants, Amelia Boynton, and also by John Lewis.

The first batch to move was a group of about 600 people who moved in groups of two. They walked to the Edmund Pettus bridge that was over the Alabama bridge and led out of Selma. They were stopped when they got to the end of the bridge and were asked to disperse within two minutes. Williams asked to see the officer in charge of the troopers who were there to stop them but the officer refused to listen saying there was nothing to talk about. Just a few moments later, they were attacked by the officers there and were overrun by horses, hit with clubs, and whipped brutally. Over 50 of these protesters including Lewis were arrested after this lash out on them.

There were cameramen who were on the ground then to video and capture these horrible moments on camera and the American Broadcasting Commission (ABC) interrupted a telecast they show regularly to air the Bloody Sunday. This roused a lot of outrage amongst Americans and protests were organized within over 70 states in America to speak against the brutalizing of innocent and peaceful protesters within the next 36-48 hours.

Following the Bloody Sunday, King and the other leaders called on Americans to come out and March some more to protest the bloody Sunday that was a clear display of the little regard that the government had for its black citizens. And while this was going on, the SCLC had its lawyers go to the court and try to get the state to not interfere with their March that was scheduled for the 9th of March, 1065. Their petition was however declined, they instead got a restraining order that was supposed to stop them from carrying on with their protest but this did not stop them from going on with their March regardless of what the state had to say. Sheriff Clark gave them a guarantee that if they agree to follow a route that will be drawn out by him for their protest and if they turn around at the end of the bridge, then there won’t be any police interference with their March. King secretly agreed as this was the only assurance of a nonviolent March for them.

On the day of the March, King followed the route given to him by the sheriff and he led the people through the bridge and stopped when the police halted them. They stopped and prayed and King turned them around to go back to Selma after the prayer in order to not violate the restraining order given to them by Wallace. Some of the protesters were angry at King when he turned them back but nothing was done about it. This day became known as the Turnaround Tuesday. Sadly, that same night, three white clergymen who came in for the protest were assaulted and one of them was killed. He came from Massachusetts, his name was James J. Reebs.

On the 15th of March, President Lyndon publicly announces support for the Selma protesters and even organized security for them to go with them all through the rest of their March. On the 17th, the judge who gave them a restraining order ruled in the favor of the protesters and they had the right to go on with their March and. The president committed to the judge that he’d send troops to go with the protesters so it doesn’t turn out the way the first two attempted ones went down. They started their March on the 21st of march and walked about 12 hours every day. They stopped and slept at fields. They walked through the rains on the 22nd and 23rd and camped in muddy fields. They arrived in Montgomery on the 25th of March and by the time they arrived, they were might by almost 50,000 supporters, both black and white.

On the final day by evening, there were thousands of people all over. They all assembled at a campsite, the City of St. Jude. A lot of prominent musicians performed like, Harry Belafonte, Nina Simone, Tony Bennette, Sammy Davis, Joan Baez, Frankie Laine among others. King gave a speech and the speech was titled “How Long Not Long”. Below is the text of the speech;

HOW LONG NOT LONG BY MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

“My dear and abiding friends, Ralph Abernathy, and to all of the distinguished Americans seated here on the rostrum, my friends and co-workers of the state of Alabama, and to all of the freedom-loving people who have assembled here this afternoon from all over our nation and from all over the world: Last Sunday, more than eight thousand of us started on a mighty walk from Selma, Alabama. We have walked through desolate valleys and across the trying hills. We have walked on meandering highways and rested our bodies on rocky byways. Some of our faces are burned from the outpourings of the sweltering sun. Some have literally slept in the mud. We have been drenched by the rains. Our bodies are tired and our feet are somewhat sore.

But today as I stand before you and think back over that great march, I can say, as Sister Pollard said a seventy-year-old Negro woman who lived in this community during the bus boycott and one day, she was asked while walking if she didn’t want to ride. And when she answered, “No,” the person said, “Well, aren’t you tired?” And with her ungrammatical profundity, she said, “My feets is tired, but my soul is rested.” And in a real sense this afternoon, we can say that our feet are tired, but our souls are rested.

They told us we wouldn’t get here. And there were those who said that we would get here only over their dead bodies, but all the world today knows that we are here and we are standing before the forces of power in the state of Alabama saying, “We ain’t goin’ let nobody turn us around.”

Now it is not an accident that one of the great marches of American history should terminate in Montgomery, Alabama. Just ten years ago, in this very city, a new philosophy was born of the Negro struggle. Montgomery was the first city in the South in which the entire Negro community united and squarely faced its age-old oppressors. Out of this struggle, more than bus desegregation was won; a new idea, more powerful than guns or clubs was born. Negroes took it and carried it across the South in epic battles that electrified the nation and the world.

Yet, strangely, the climactic conflicts always were fought and won on Alabama soil. After Montgomery’s, heroic confrontations loomed up in Mississippi, Arkansas, Georgia, and elsewhere. But not until the colossus of segregation was challenged in Birmingham did the conscience of America begin to bleed. White America was profoundly aroused by Birmingham because it witnessed the whole community of Negroes facing terror and brutality with majestic scorn and heroic courage. And from the wells of this democratic spirit, the nation finally forced Congress to write legislation in the hope that it would eradicate the stain of Birmingham. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 gave Negroes some part of their rightful dignity, but without the vote, it was dignity without strength.

Once more the method of nonviolent resistance was unsheathed from its scabbard, and once again an entire community was mobilized to confront the adversary. And again the brutality of a dying order shrieks across the land. Yet, Selma, Alabama, became a shining moment in the conscience of man. If the worst in American life lurked in its dark streets, the best of American instincts arose passionately from across the nation to overcome it. There never was a moment in American history more honorable and more inspiring than the pilgrimage of clergymen and laymen of every race and faith pouring into Selma to face danger at the side of its embattled Negroes.

The confrontation of good and evil compressed in the tiny community of Selma generated the massive power to turn the whole nation to a new course. A president born in the South had the sensitivity to feel the will of the country, and in an address that will live in history as one of the most passionate pleas for human rights ever made by a president of our nation, he pledged the might of the federal government to cast off the centuries-old blight. President Johnson rightly praised the courage of the Negro for awakening the conscience of the nation.

On our part, we must pay our profound respects to the white Americans who cherish their democratic traditions over the ugly customs and privileges of generations and come forth boldly to join hands with us. From Montgomery to Birmingham, from Birmingham to Selma, from Selma back to Montgomery a trail wound in a circle long and often bloody, yet it has become a highway up from the darkness. Alabama has tried to nurture and defend evil, but evil is choking to death in the dusty roads and streets of this state. So I stand before you this afternoon with the conviction that segregation is on its deathbed in Alabama, and the only thing uncertain about it is how costly the segregationists and Wallace will make the funeral.

Our whole campaign in Alabama has been centered around the right to vote. In focusing the attention of the nation and the world today on the flagrant denial of the right to vote, we are exposing the very origin, the root cause, of racial segregation in the Southland. Racial segregation as a way of life did not come about as a natural result of hatred between the races immediately after the Civil War. There were no laws segregating the races then. And as the noted historian, C. Vann Woodward, in his book, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, clearly points out, the segregation of the races was really a political stratagem employed by the emerging Bourbon interests in the South to keep the southern masses divided and southern labor the cheapest in the land. You see, it was a simple thing to keep the poor white masses working for near-starvation wages in the years that followed the Civil War. Why, if the poor white plantation or mill worker became dissatisfied with his low wages, the plantation or mill owner would merely threaten to fire him and hire former Negro slaves and pay him even less. Thus, the southern wage level was kept almost unbearably low.

Toward the end of the Reconstruction era, something very significant happened. That is what was known as the Populist Movement. The leaders of this movement began awakening the poor white masses and the former Negro slaves to the fact that they were being fleeced by the emerging Bourbon interests. Not only that, but they began uniting the Negro and white masses into a voting bloc that threatened to drive the Bourbon interests from the command posts of political power in the South.

To meet this threat, the southern aristocracy began immediately to engineer this development of a segregated society. I want you to follow me through here because this is very important to see the roots of racism and the denial of the right to vote. Through their control of mass media, they revised the doctrine of white supremacy. They saturated the thinking of the poor white masses with it, thus clouding their minds to the real issue involved in the Populist Movement. They then directed the placement on the books of the South of laws that made it a crime for Negroes and whites to come together as equals at any level. And that did it. That crippled and eventually destroyed the Populist Movement of the nineteenth century.

If it may be said of the slavery era that the white man took the world and gave the Negro Jesus, then it may be said of the Reconstruction era that the southern aristocracy took the world and gave the poor white man Jim Crow. He gave him Jim Crow And when his wrinkled stomach cried out for the food that his empty pockets could not provide, he ate Jim Crow, a psychological bird that told him that no matter how bad off he was, at least he was a white man, better than the black man. And he ate Jim Crow. And when his undernourished children cried out for the necessities that his low wages could not provide, he showed them the Jim Crow signs on the buses and in the stores, on the streets, and in the public buildings. And his children, too, learned to feed upon Jim Crow, (Speak) their last outpost of psychological oblivion.

Thus, the threat of the free exercise of the ballot by the Negro and the white masses alike resulted in the establishment of a segregated society. They segregated southern money from the poor whites; they segregated southern mores from the rich whites; they segregated southern churches from Christianity; they segregated southern minds from honest thinking, and they segregated the Negro from everything. That’s what happened when the Negro and white masses of the South threatened to unite and build a great society: a society of justice where none would pray upon the weakness of others; a society of plenty where greed and poverty would be done away; a society of brotherhood where every man would respect the dignity and worth of human personality.

We’ve come a long way since that travesty of justice was perpetrated upon the American mind. James Weldon Johnson put it eloquently. He said:

We have come over a way

That with tears hath been watered.

We have come treading our paths

Through the blood of the slaughtered.

Out of the gloomy past,

Till now we stand at last

Where the white gleam

Of our bright star is cast.

Today I want to tell the city of Selma, today I want to say to the state of Alabama, today I want to say to the people of America and the nations of the world, that we are not about to turn around. We are on the move now.

Yes, we are on the move and no wave of racism can stop us. We are on the move now. The burning of our churches will not deter us. The bombing of our homes will not dissuade us. We are on the move now. The beating and killing of our clergymen and young people will not divert us. We are on the move now. The wanton release of their known murderers would not discourage us. We are on the move now. Like an idea whose time has come, not even the marching of mighty armies can halt us. We are moving to the land of freedom.

Let us, therefore, continue our triumphant march to the realization of the American dream. Let us march on segregated housing until every ghetto or social and economic depression dissolves, and Negroes and whites live side by side in decent, safe, and sanitary housing. Let us march on segregated schools until every vestige of segregated and inferior education becomes a thing of the past, and Negroes and whites study side-by-side in the socially healing context of the classroom.

Let us march on poverty until no American parent has to skip a meal so that their children may eat. March on poverty until no starved man walks the streets of our cities and towns in search of jobs that do not exist. Let us march on poverty until wrinkled stomachs in Mississippi are filled, and the idle industries of Appalachia are realized and revitalized, and broken lives in sweltering ghettos are mended and remolded.

Let us march on ballot boxes, march on ballot boxes until race-baiters disappear from the political arena.

Let us march on ballot boxes until the salient misdeeds of bloodthirsty mobs will be transformed into the calculated good deeds of orderly citizens.

Let us march on ballot boxes until the Wallaces of our nation tremble away in silence.

Let us march on ballot boxes until we send to our city councils, state legislatures, and the United States Congress, men who will not fear to do justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with thy God.

Let us march on ballot boxes until brotherhood becomes more than a meaningless word in an opening prayer, but the order of the day on every legislative agenda.

Let us march on ballot boxes until all over Alabama God’s children will be able to walk the earth in decency and honor.

There is nothing wrong with marching in this sense. The Bible tells us that the mighty men of Joshua merely walked about the walled city of Jericho and the barriers to freedom came tumbling down. I like that old Negro spiritual, “Joshua fought the Battle of Jericho.” In its simple, yet colorful, depiction of that great moment in biblical history, it tells us that:

Joshua fought the battle of Jericho,

Joshua fought the battle of Jericho,

And the walls come tumbling down.

Up to the walls of Jericho, they marched, spear in hand.

“Go blow them ram horns,” Joshua cried,

“‘Cause, the battle is in my hand.”

These words I have given you just as they were given us by the unknown, long-dead, dark-skinned originator. Some now long-gone black bard bequeathed to posterity these words in ungrammatical form, yet with emphatic pertinence for all of us today.

The battle is in our hands. And we can answer with creative nonviolence the call to higher ground to which the new directions of our struggle summons us. The road ahead is not altogether a smooth one. There are no broad highways that lead us easily and inevitably to quick solutions. But we must keep going.

In the glow of the lamplight on my desk a few nights ago, I gazed again upon the wondrous sign of our times, full of hope and promise of the future. And I smiled to see in the newspaper photographs of many a decade ago, the faces so bright, so solemn, of our valiant heroes, the people of Montgomery. To this list may be added the names of all those who have fought and, yes, died in the nonviolent army of our day: Medgar Evers, three civil rights workers in Mississippi last summer, William Moore, as has already been mentioned, the Reverend James Reeb, Jimmy Lee Jackson, and four little girls in the church of God in Birmingham on Sunday morning. But in spite of this, we must go on and be sure that they did not die in vain. The pattern of their feet as they walked through Jim Crow barriers in the great stride toward freedom is the thunder of the marching men of Joshua, and the world rocks beneath their tread.

My people, my people, listen. The battle is in our hands. The battle is in our hands in Mississippi and Alabama and all over the United States. I know there is a cry today in Alabama, we see it in numerous editorials: “When will Martin Luther King, SCLC, SNCC, and all of these civil rights agitators and all of the white clergymen and labor leaders and students and others get out of our community and let Alabama return to normalcy?”

But I have a message that I would like to leave with Alabama this evening. That is exactly what we don’t want, and we will not allow it to happen, for we know that it was normalcy in Marion that led to the brutal murder of Jimmy Lee Jackson. It was normalcy in Birmingham that led to the murder on Sunday morning of four beautiful, unoffending, innocent girls. It was normalcy on Highway 80 that led state troopers to use tear gas and horses and billy clubs against unarmed human beings who were simply marching for justice. It was normalcy by a cafe in Selma, Alabama, that led to the brutal beating of Reverend James Reeb.

It is normalcy all over our country which leaves the Negro perishing on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of vast ocean of material prosperity. It is normalcy all over Alabama that prevents the Negro from becoming a registered voter. No, we will not allow Alabama to return to normalcy.

The only normalcy that we will settle for is the normalcy that recognizes the dignity and worth of all of God’s children. The only normalcy that we will settle for is the normalcy that allows judgment to run down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream. The only normalcy that we will settle for is the normalcy of brotherhood, the normalcy of true peace, the normalcy of justice.

And so as we go away this afternoon, let us go away more than ever before committed to this struggle and committed to nonviolence. I must admit to you that there are still some difficult days ahead. We are still in for a season of suffering in many of the black belt counties of Alabama, many areas of Mississippi, many areas of Louisiana. I must admit to you that there are still jail cells waiting for us, and dark and difficult moments. But if we will go on with the faith that nonviolence and its power can transform dark yesterdays into bright tomorrows, we will be able to change all of these conditions.

And so I plead with you this afternoon as we go ahead: remain committed to nonviolence. Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man but to win his friendship and understanding. We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.

I know you are asking today, “How long will it take?” Somebody’s asking, “How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding, and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne?” Somebody’s asking, “When will wounded justice, lying prostrate on the streets of Selma and Birmingham and communities all over the South, be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men?” Somebody’s asking, “When will the radiant star of hope be plunged against the nocturnal bosom of this lonely night, plucked from weary souls with chains of fear and the manacles of death? How long will justice be crucified, and truth bear it?”

I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because “truth crushed to earth will rise again.”

How long? Not long, because “no lie can live forever.”

How long? Not long, because “you shall reap what you sow.”

How long? Not long,

Truth forever on the scaffold,

Wrong forever on the throne,

Yet that scaffold sways the future,

And, behind the dim unknown,

Standeth God within the shadow,

Keeping watch above his own.

How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.

How long? Not long, because:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He has loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword;

His truth is marching on.

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment seat.

Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! Be jubilant my feet!

Our God is marching on.

Glory, hallelujah! Glory, hallelujah!

Glory, hallelujah! Glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on.

After King delivered his speech, he and the remaining people marched to the entrance of the capitol with a petition for the governor but the troops blocked the entrance and stopped them from entering. They waited until the governor’s secretary came and took the petition. This march was the most successful of all the marches that have been organized. this was without any violence or harassment with no arrests made.

After the march, on the 6th of August 1965, the voting rights act was passed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. This act allowed African Americans and non-whites to vote without having to take any literacy test or go through the complicated process of voter registration. The registration was open to all without any difference of color or race, religion or sex. There was a ceremony to commemorate this great event which had Martin Luther King Jr. in attendance along with other black leaders who were happy to have finally made progress despite the obstacles they encountered in their quest.

KING OPPOSES THE VIETNAM WAR

Martin Luther King was never in support of America supporting the Vietnamese war and even deploying soldiers to go help with the war. King was reluctant to air his opinions publicly but he went public after being convinced by former SCLC leader, James Bevel. King gave a speech on the 4th of April, 1967 in Riverside Church in New York City. This was coincidentally exactly one year to his death. The speech he gave was titled ” Beyond Vietnam: A Time To Break The Silence”. Below is the speech King gave at the meeting :

BEYOND VIETNAM: A TIME TO BREAK THE SILENCE

Mr. Chairman, ladies, and gentlemen, I need not pause to say how very delighted I am to be here tonight, and how very delighted I am to see you expressing your concern about the issues that will be discussed tonight by turning out in such large numbers. I also want to say that I consider it a great honor to share this program with Dr. Bennett, Dr. Commager, and Rabbi Heschel, some of the distinguished leaders and personalities of our nation. And of course, it’s always good to come back to Riverside Church. Over the last eight years, I have had the privilege of preaching here almost every year in that period, and it is always a rich and rewarding experience to come to this great church and

this great pulpit.

I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice. I join you in this meeting because I am in deepest agreement with the aims and work of the organization which has brought us together, Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam. The recent statements of your executive committee are the sentiments of my own heart, and I found myself in full accord when I read its opening lines: “A time comes when silence is betrayal.” That time has come for us in relation to Vietnam.